The Omicron variant spreads even more rapidly than do earlier variants of Covid, which were themselves highly transmissible.

However, after about a month, the number of people in a particular place who are infected with the omicron variant peaks and then rapidly declines.

In the USA, omicron began to sweep through the population in mid-December.

This probably means that in mid-January, throughout the USA, the number of daily infections will begin to fall.

However, because the number of hospitalizations from Covid lags behind case rates by two weeks, this might mean that hospitalizations will peak in early February.

This could mean that much of the healthcare infrastructure in the USA will literally begin to collapse around the beginning of February.

.

A greater question is whether this disintegration of many basic services will also be true of other crucial sectors of society — especially those reliant on essential workers.

One popular argument is that because the omicron variant is not as harshly virulent as the earlier forms of Covid were — especially thanks to vaccines — then its spread should be encouraged.

The problem with this argument is that if a large chunk of the American population is somewhat ill all at the same time, society will temporarily cease to function.

.

One of the perceptions surrounding the response to omicron variant is that its virulence is being downplayed by healthcare authorities as a favor to business interests.

In particular, the CDC has recommended that the isolation period for those with mild Covid be reduced to five days, followed by five days of mask wearing.

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s1227-isolation-quarantine-guidance.html

Given what we currently know about COVID-19 and the Omicron variant, CDC is shortening the recommended time for isolation for the public. People with COVID-19 should isolate for 5 days and if they are asymptomatic or their symptoms are resolving (without fever for 24 hours), follow that by 5 days of wearing a mask when around others to minimize the risk of infecting people they encounter. The change is motivated by science demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.

However, if there is a pragmatic motive that is influencing this policy change, it is not the sacrifice of lives for the sake of business profit.

The pragmatic motive is the fear of serious societal disruption.

.

The omicron variant poses a scenario out of the most subtle of plots in science fiction.

Imagine a plague that does not necessarily kill many people, but makes everybody somewhat ill during a one month period, during which time they cannot work for a week.

Civilization would begin to stumble and then crumble during this brief period, although without completely collapsing.

That scenario of limited societal disintegration was not true even during lockdowns in 2020, when essential services remained intact despite a significant death toll.

However, with omicron, at any given time during its initial surge, a large fraction of essential workers are out of the picture, if only briefly.

.

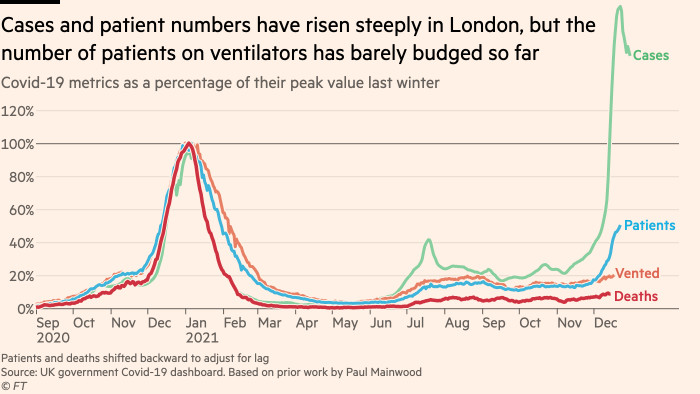

During 2020, there was a call to “flatten the curve” in order to protect the healthcare system from becoming overwhelmed with patients on ventilators in the ICUs.

In the first month of 2022, hospitals are once again being overrun — not necessarily in their ICUs, but in their emergency rooms, with Covid patients.

In the USA, in particular, the lack of testing infrastructure means that people who want to be tested for Covid are going to the hospitals to do so (and sometimes getting infected).

But more than relieving pressure on hospitals, in January, 2022, the goal is to get back to work for the sake of society.

That is, hospitals might indeed begin to fail and collapse as staff become ill and patients overwhelm the system.

But the greater concern would be that essential services might begin to disintegrate during the month of January.

https://www.ft.com/content/d07f4559-f4f5-4063-94e7-c322bdcf62ce

.

There have been complaints that the CDC is not adequately articulating the science behind its five-day isolation recommendation.

However, even when the science is relatively sound, the nature of public health messaging is to simplify a complex reality — often to the point that the simple message becomes problematic.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/us/politics/cdc-rochelle-walensky-covid-isolation-testing.html

“I don’t think that the C.D.C. guidelines were significantly wrong,” Dr. Tom Frieden, the agency’s director under former President Barack Obama, said of the latest recommendations on isolation for those with Covid. But he added, “I think the way they were released was very problematic.”

Dr. Frieden said there were three rules to putting out public health guidance: it must be technically correct, simple and workable in the real world.

Although real world conditions shape the message, they are not mentioned in the message for the sake of simplicity.

Dr. Walensky certainly had real-world implications to consider: Would it make sense to recommend that people take Covid tests, when they are so hard to find? And with so many people getting infected with Omicron, encouraging them all to stay home for longer than five days could cripple the economy.

.

Thus, the issue might be that the CDC is not communicating how its views on omicron take into account the specter of real societal unraveling, if only for a month.

This “omicron scenario” is not being communicated by authorities probably because it is complicated and overwhelming — and also because it lies beyond the scope of the natural sciences.

That is, the Biden administration and the CDC promised to just stick with science.

Thus, insofar as the societal ramifications of omicron lie outside of epidemiology, it is not put at the forefront of public discussion.

.

In sum, the goal during the time of omicron is to get back to work as soon as possible after getting sick in order to protect the socioeconomic order from disintegration.

This time, extraordinary measures are not being called for in order to inhibit the spread of the virus.

Notably, there is currently no public call to “flatten the curve” to save civilization.

Importantly, the context of this silence is a society that often resists basic measures — such as masks, vaccines, and tests — that would slow the spread of omicron (and the seasonal flu, as well).

Because basic precautions are only haphazardly observed in American society, the quality and quantity of masks and tests are limited — which makes flattening the curve so much harder.

This is not simply an administrative bungling or a failure of messaging.

Rather, it is a bottom-up, grassroots complacency that distorts pandemic policy.

We cannot take basic precautions in order to flatten the curve to save essential workers because we just don’t feel like it.

Because we won’t flatten the curve, when we inevitably all get sick at the same time, we need to get back to work as soon as possible to prevent societal disintegration.

.

All of this revolves around the central role played by essential workers.

Again, in the dark days of 2020, prior to the vaccines, essential workers kept society functioning even during periods of lockdown, when everyone else was sheltering.

During this period, essential workers suffered disproportionately high death rates, but they kept going to work.

With omicron, the death rate might be much lower — but so many people are missing work because so many people are infected.

(For example, New York City Mayor Eric Adams stated that 20% of the city’s police force is currently infected with Covid.)

.

Omicron should therefore be understood and framed as a threat to essential workers and the work they do.

Yet, this issue is not visible in the media.

In fact, essential workers themselves seem comparatively invisible to the media when one considers all the issues related to essential workers that go unaddressed.

For example, essential workers are dissuaded from quitting because they would not be eligible for unemployment benefits.

The general rule of unemployment has always been that you can’t collect benefits if you quit your job. But what about during a pandemic, when going to work means putting your life at risk?

Apparently, the rule still applies.

As nonessential workers across the country are being recalled to their jobs, they’re experiencing a similar scenario: Sure, you can quit or decline to go back, but that means no more unemployment insurance.

Because there was a scarcity of job openings during the pandemic, essential workers could not quit their jobs and find other jobs — effectively turning them into forced labor.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/05/21/essential-workers-pay-wages-safety-unemployment/

For nurses, grocery clerks and transportation workers, quitting is not an option right now. The irony is that while these workers are — in the word of the moment — “essential” to consumers and employers, they have zero leverage in the workplace. That’s because the coronavirus pandemic has destroyed almost all the alternative jobs. There’s nowhere to go.

The situation is so stark that we can ask whether extreme economic circumstances have turned the workers we call heroes into something closer to forced labor. If so, that realization ought to shape our public policies: A just society owes much more than minimal pay and a few plexiglass shields to the citizens — and noncitizens — it compels into service.

Moreover, in the USA, hazard pay for essential workers is irregular and uncertain.

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/whos-a-hero-some-states-cities-still-debating-hazard-pay

When the U.S. government allowed so-called hero pay for frontline workers as a possible use of pandemic relief money, it suggested occupations that could be eligible from farm workers and childcare staff to janitors and truck drivers.

State and local governments have struggled to determine who among the many workers who braved the raging coronavirus pandemic before vaccines became available should qualify: Only government workers, or private employees, too? Should it go to a small pool of essential workers like nurses or be spread around to others, including grocery store workers?

.

Compelling essential workers to work during a pandemic might be necessary, but it should be compensated with benefits, such as hazard pay.

Another benefit would be state provisions for basic health insurance.

For conservatives, public health care would create “moral hazard” because it would be granted in some cases to those who do not work — and thus presumably do not deserve it.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/02/is-health-care-a-right

However, most Americans might agree that some limited form of publicly funded healthcare is justly deserved for those who work in essential services.

Public health care for essential workers would not violate moral hazard.

In fact, it would be similar to the benefits granted to members of the military.

Minimal health care provisions for all people might also be needed for pandemic preparedness in order to get people to see a doctor and take tests that would be free.

.

Indeed, this highlights the role of public health in terms of national security.

The relationship between public health and national security also means that essential workers would subject to vaccine mandates.

As they used to say back during the world wars, “You’re in the army now”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You%27re_in_the_Army_Now_(song)