It's owners continued to run it as if it were a small business, even as the company surpassed its own grandiose ambitions.

Forever 21 pioneered a new category of retail -- "fast fashion".

Fast fashion is dirt-cheap yet trendy.

Fast fashion, however, is not an example of "disruptive innovation".

Disruptive innovation consists of an obscure, cheap and inferior market that is entirely outside the mainstream finding a niche and improving over time until finally, and unexpectedly, it displaces the dominant market.

Fast fashion was actually the lower end of the incumbent market, and not a distinct market.

Mainstream corporations imitated Forever 21 and stole its fire.

This might be part of a larger pattern.

It is a pattern that one finds in the evolution of amusement parks, of the mafia and of Las Vegas:

A crude, small-time operation becomes big-time and corporate, then gets displaced by corporations from the mainstream.

That is, mainstream corporations appropriate a new product category that was pioneered by a outsider.

Is this now happening to Tesla?

Tesla, like Forever 21, is not an example of classic disruptive innovation.

However, Tesla is not at the low end of the mainstream market.

Like Uber, Tesla is actually at the high end of the mainstream market and working furiously to move downmarket and make its products available to ordinary people.

Unfortunately for Tesla, ordinary Americans are mostly not interested in sporty electric cars.

Ordinary Americans are smitten with big, bulky trucks.

That might even be true if Tesla makes futuristic trucks.

It will be affluent tech workers from Silicon Valley who will buy Tesla's trucks, just as they are the market for Tesla's cars.

Tesla may not pose an immediate threat to the mainstream auto and truck market in the USA.

However, Tesla is eating away at market share in high end vehicles.

In this way, Tesla is a bit like the Apple Watch.

The Apple Watch seems to be displacing Swiss watches.

https://www.ft.com/content/eda695f0-516b-11ea-90ad-25e377c0ee1f

According to research firm Strategy Analytics, the Apple Watch, launched less than five years ago, now outsells the entire Swiss industry, which has been manufacturing wristwatches for 152 years. Last year, Apple increased sales by 36 per cent to almost 31m watches while the Swiss industry shipped about 21m in total, a 13 per cent decline.

The one solace for Swiss watchmakers is that they still generate more revenue: $21bn to Apple’s $11bn. But on current trends Apple will overtake the Swiss on that measure, too, by 2023.However, there are different market segments in the wristwatch industry.

The low end of the wristwatch industry may be obsolete due to the rise of the smartphone.

That is classic disruptive innovation.

The new, disruptive product -- a clock you inconveniently keep in your pocket -- might not be perfect, but it is free.

To the ordinary person, a free portable digital clock is more valuable than the cheapest of wristwatches.

In contrast, the low end of the luxury wristwatch market is being disrupted by smartwatches.

The Apple Watch is killing Rolex at its low end.

But the high end of the luxury wristwatch market is doing better than ever.

René Weber, a luxury analyst at Bank Vontobel in Zurich, highlights the sharp contrast in performance between the low and high-end watch segments. Since 2000, Swiss watches costing less than $1,000 have seen their unit sales halve, while watches costing more than $5,000 have seen volumes triple.

Mr Weber says sales of the most prestigious watches made by Rolex, Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet have been little affected by the smartwatch revolution. Indeed, there are waiting lists for some of their top-end products because of capacity constraints in manufacturing complex mechanical watches.

“You buy these Swiss watches for eternity, whereas you throw away a smartwatch after two to three years,” he says. “It is a different kind of watch, a different kind of experience.”The flourishing of a luxury market at the high-end might represent a backlash to the democratization of luxury at the low end.

That is, what might be perceived as the product of growing inequality might actually (or might also) signify the devaluation of moderate luxury as it becomes more accessible.

The problem would be growing equality and a rise of status anxiety among those who were most affluent.

For example, higher levels of educational attainment reflect growing equality.

However, those higher educational attainment rates makes it that much more of an imperative for people to send their kids to the most expensive schools.

Since lower-division students are basically reading the same textbooks wherever they go, there is an increasing emphasis on luxurious amenities to distinguish schools.

So the obsession with exaggerating status symbols at the high end reflects increasing democratization in the middle (e.g., smartwatches, state universities).

Indeed, the democratization of the smartwatch market has been taking place since the introduction of the Apple Watch.

That is, the price of the Apple Watch has been falling since its release in 2015.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/26/fashion/watches-design-audemars-piguet-apple-watch.html

Initially positioned as a luxury product, with an 18-karat gold version that started at $10,000, the watch now starts at a new low price of $199 and is promoted as a health and fitness tool.Another motive behind the growth of high-end luxury would be the desperation of incumbents who find themselves being disrupted.

Incumbent industries find themselves faced with a choice between adopting a new disruptive innovation or somehow competing against it.

Adopting a cheap, alien technology is neither what an incumbent wants to do nor even what the incumbent is capable of doing.

The rise of digital watches in the 1980s is an example of this.

The Swiss doubled down on sticking with mechanical watches.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quartz_crisis

In watchmaking, the quartz crisis (or quartz revolution) is the upheaval in the industry caused by the advent of quartz watches in the 1970s and early 1980s, that largely replaced mechanical watches around the world.[1][2] It caused a significant decline of the Swiss watchmaking industry, which chose to remain focused on traditional mechanical watches, while the majority of the world's watch production shifted to Asian companies such as Seiko, Citizen and Casio in Japan that embraced the new electronic technology.One strategy is to try to undercut the disruptive innovation on price.

This is exemplified by the creation of the Swatch in the 1980s.

The Swatch was an attempt to compete against cheap digital watches by making accessible, trendy, entry-level mechanical watches.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swatch

Swatch (stylized as swatch) is a Swiss watchmaker founded in 1983 by Nicolas Hayek and a subsidiary of The Swatch Group. The Swatch product line was developed as a response to the "quartz crisis" of the 1970s and 1980s, in which Asian-made digital watches were competing against traditional European-made mechanical watches.

The name Swatch is a contraction of "second watch",[1] as the watches were intended as casual, disposable accessories.The other strategy is to move upmarket.

This is "sustaining innovation", in which established products are improved upon.

https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

Disruption theory differentiates disruptive innovations from what are called “sustaining innovations.” The latter make good products better in the eyes of an incumbent’s existing customers: the fifth blade in a razor, the clearer TV picture, better mobile phone reception. These improvements can be incremental advances or major breakthroughs, but they all enable firms to sell more products to their most profitable customers.The iPhone -- the quintessential disruptor -- is itself an example of how incumbents flee upmarket in the face of disruption.

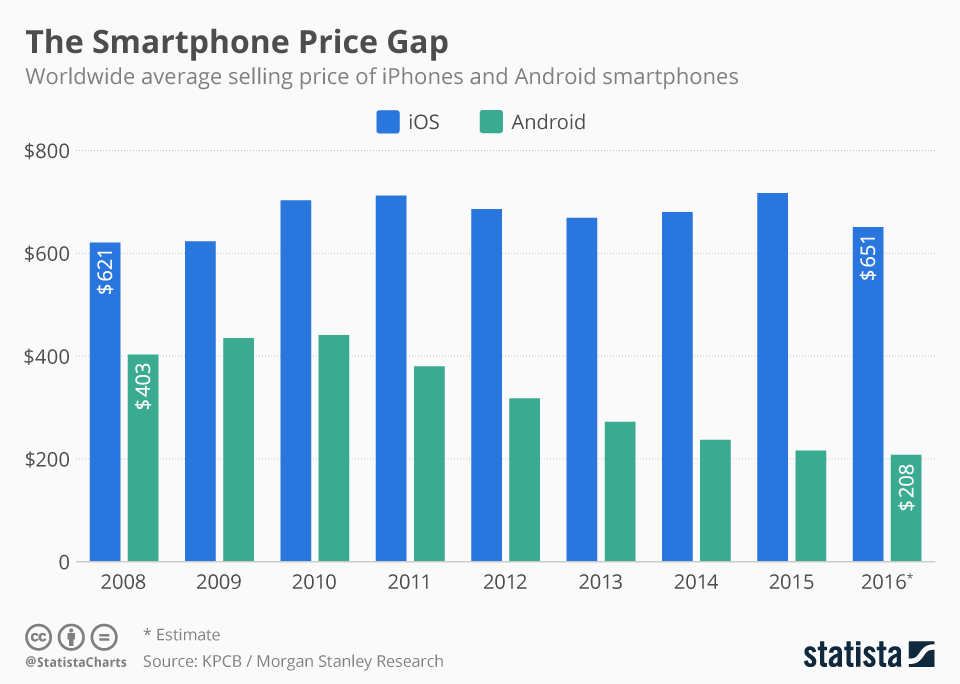

The cost of Adroid phones keeps falling.

Apple's response in 2017 was to create the $999 iPhone X.

The falling cost of technology exemplified in Android phones might be a result of "efficiency innovation".

https://hbr.org/2014/06/the-capitalists-dilemma

Efficiency innovations help companies make and sell mature, established products or services to the same customers at lower prices. Some of these innovations are what we have elsewhere called low-end disruptions, and they involve the creation of a new business model. Walmart was a low-end disrupter in retailing, for example, and Geico in insurance. Other innovations, such as Toyota’s just-in-time production system, are process improvements. Efficiency innovations play two important roles. First, they raise productivity, which is essential for maintaining competitiveness but has the painful side effect of eliminating jobs. Second, they free up capital for more-productive uses.

Toyota’s production system, for example, allowed the automaker to operate with two months’—rather than two years’—worth of inventory on hand, which freed up massive amounts of cash.Eventually, improved efficiency will push down the cost of smartwatches so that they will become as ubiquitous as smartphones.

In the light of all of the above, it seems counterintuitive that Tesla is trying to manufacture electric cars for the ordinary "everyman".

That sort of mass production is too stressful, and undermines Tesla's image as futuristic and exclusive.

https://www.businessinsider.com/some-tesla-workers-say-company-has-made-big-production-mistakes-2020-3

It is thus puzzling that a luxury brand like Tesla would try to move downmarket as it has with the Model 3.

Rather, as with iPhones and Rolexes, the conventional strategy would be for Tesla to move relentlessly upmarket.

Tesla's move downmarket reflects Elon Musk's impatient desire to transform the auto industry.

Little does Musk seem to realize that he has already triggered the future transformation of the automobile industry into pure EV production.

The popularity of Tesla's high-end cars among luxury auto buyers seems to be exerting pressure on luxury car manufacturers.

Thus, the high-end of automobile manufacturing seems to be shifting toward EV production.

This acceptance of EVs in the luxury market is happening prior to broad acceptance of EVs in the middle and low end of the American automobile market.

The conquest of luxury car markets by EVs might transform EV technology and its public image.

Eventually, EVs may become both affordable and acceptable to ordinary Americans, who currently reject concerns about fuel economy and the environment.

That is, efficiency innovation will drive down EV costs gradually, so that what was a luxury vehicle will become a car for everyone.

Again, one sees this with global smartphone prices falling by 5% a year since the iPhone was launched in 2007.

But this is the dilemma that has always faced innovative companies like Tesla.

On the one hand, the innovator faces an industry paranoid about change, and that industry will try to drive the innovator out of business.

On the other hand, the status quo will eventually adopt the new idea and drive the original innovator out of business.

The third stage of this process is when the innovator ends up working for the establishment.

["Tucker: The Man and His Dream", 1988, trailer]

The movie "Tucker" was directed by Francis Ford Coppola and produced by George Lucas.

Coppola and Lucas were young outsiders and great creative filmmakers during the rebellious "New Hollywood" of the 1970s.

Coppola and Lucas were eventually absorbed into mainstream Hollywood.

Perhaps Elon Musk will end up working at Ford.