The 2020 recession

The economist Nouriel Roubini argues that there is going to be a recession in 2020. Unfortunately, at some point the USA will not be able to use the usual stimulus measures to revive the economy. This is because there will be several "permanent supply shocks" at work, including trade and technology conflict between the USA and China, as well as military conflict between the USA and Iran that would lead to rising oil prices. In the face of inflation, the USA will not be able stimulate the economy in the midst of recession because this could trigger hyperinflation.https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/aug/23/global-recession-immune-monetary-solution-negative-supply-shock

All three of these potential shocks would have a stagflationary effect, increasing the price of imported consumer goods, intermediate inputs, technological components and energy, while reducing output by disrupting global supply chains. Worse, the Sino-American conflict is already fuelling a broader process of deglobalisation, because countries and firms can no longer count on the long-term stability of these integrated value chains. As trade in goods, services, capital, labour, information, data and technology becomes increasingly balkanized, global production costs will rise across all industries.Roubini is know as "Dr. Doom" because he is a pessimist. As far back as 2005 he accurately predicted the meltdown in real estate and financial markets. Roubini worked in the Clinton administration, and is associated with the Democratic Party.

Here is a list of economists who accurately predicted the 2008 meltdown:

https://www.businesstoday.in/top-story/these-people-predicted-the-2008-recession-and-were-laughed-at/story/283071.html

It is said that very few economists foresaw the financial crisis of 2008. Actually, quite a few topnotch economists predicted the 2008 crisis. The problem was that few listened.

Just prior to that crisis, the premier economist within the Republic Party was David Rosenberg. He accurately explained why the USA was headed into the worst recession in its history. He is again saying something like that now. For instance, there is a bubble in corporate debt.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2019/04/08/what-ballooning-corporate-debt-means-for-investors/#11869fa9636c

Since the last recession, nonfinancial corporate debt has ballooned to more than $9 trillion as of November 2018, which is nearly half of U.S. GDP. As you can see below, each recession going back to the mid-1980s coincided with elevated debt-to-GDP levels—most notably the 2007-2008 financial crisis, the 2000 dot-com bubble and the early '90s slowdown.

Through 2023, as much as $4.88 trillion of this debt is scheduled to mature. And because of higher rates, many companies are increasingly having difficulty making interest payments on their debt, which is growing faster than the U.S. economy, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF).

On top of that, the very fastest-growing type of debt is riskier BBB-rated bonds—just one step up from “junk.” This is literally the junkiest corporate bond environment we’ve ever seen.

Combine this with tighter monetary policy, and it could be a recipe for trouble in the coming months.Along with the bubble in corporate debt, there is a bubble in consumer spending. Earnings are down, and spending is being financed by borrowing.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/08/21/consumer-spending-is-a-bubble-waiting-to-burst-david-rosenberg-warns.html

“What no one seems to talk about is the underlying fundamentals behind the consumer are actually deteriorating before our very eyes,” the firm’s chief economist and strategist said Tuesday on CNBC’s “Futures Now. ”

Yet the latest economic data suggests the consumer, considered the main driver of the U.S. economy, is on solid ground. Commerce Department figures show retail sales in July rose 0.7%, after a 0.3% increase in June.

In a recent note, Rosenberg criticized the government’s retail report. He estimated the bullish retail sales number was completely financed by credit and, therefore, unsustainable.

According to Rosenberg, the problems lie in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ real average weekly earnings decline in July of 0.3% from June.

“It’s actually been flat to down now in six of the past eight months,” said Rosenberg. “I’m actually wondering how long the consumer is actually going to keep it up and hold the glue together for the economy when real incomes are starting to subside as much as they are.”In order to maintain a middle-class lifestyle, Americans are going into debt.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/families-go-deep-in-debt-to-stay-in-the-middle-class-11564673734?mod=rsswn

The American middle class is falling deeper into debt to maintain a middle-class lifestyle.

Cars, college, houses and medical care have become steadily more costly, but incomes have been largely stagnant for two decades, despite a recent uptick. Filling the gap between earning and spending is an explosion of finance into nearly every corner of the consumer economy.

Average tuition at public four-year colleges, however, went up 549%, not adjusted for inflation, according to data from the College Board. On the same basis, average per capita personal health-care expenditures rose about 276% over a slightly shorter period, 1990 to 2017, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.Growing debt reflects confidence in the economy, but when borrowers bet wrong and the economy sours, debt blows up in their face -- and in the economy. The crucial question is whether the debt is paying for investments or for luxuries. Going into debt to buy status symbols makes people poorer, and this increases wealth inequality.

And average housing prices swelled 188% over those three decades, according to the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index.

Taking on a mortgage to buy a house that could appreciate, or borrowing for a college degree that should boost earning power, can be wise decisions. Borrowing for everyday consumption or for assets such as cars that lose value makes it harder to save and invest in stocks and real estate that tend to create wealth. So the rise in consumer borrowing exacerbates the wealth gap.A case study suggests that typical borrowing is for both investments and luxury.

Jonathan Guzman and Mayra Finol earn about $130,000 a year, combined, in technology jobs. Though that is more than double the median, debt from their years at St. John’s University in New York has been hard to overcome.

The two 28-year-olds in West Hartford, Conn., have about $51,000 in student debt, plus $18,000 in auto loans and $50,000 across eight credit cards. Adding financial pressure are a baby daughter and a mortgage of around $270,000.

“I’m normally a worrier, but this is next-level stuff. I’ve never been more stressed,” Mr. Guzman said. “Never would I have thought with the amount we make I would have these problems.”

They no longer dine out several times a week. Other hits to their budget were hard to avoid, such as a wrecked car that forced them to borrow more.First of all, these are not middle class people, they are the upper-middle class. Second, in an earlier generation, middle class people did not eat out several times a week, they ate out maybe several times a month or several times a year. And when they did dine out, they ate food like chicken and waffles.

https://www.laweekly.com/what-to-eat-during-hbos-mildred-pierce-a-fried-chicken-recipe/

Cars (actually, trucks and SUVs)

The rising price of automobiles is telling, and so is the rising method of paying for cars -- borrowing.Nowhere is the struggle to maintain a middle-class lifestyle more apparent than in cars. The average new-car price in the U.S. was $37,285 in June, according to Kelley Blue Book. It didn’t deter buyers. The industry sold or leased at least 17 million cars each year from 2015 to 2018, its best four-year stretch ever. Partly because of demand satisfied by that run, sales are projected to be off modestly this year.

How households earning $61,000 can acquire cars costing half their gross income is a story of the financialization of the economy. Some 85% of new cars in the first quarter of this year were financed, including leases, according to Experian. That is up from 76% in the first quarter of 2009.

Car trouble

And 32% of new-car loans were for six to seven years. A decade ago, only 12% were that long. The shorter-term loans of the past gave many owners several years of driving without car payments.

Now, a third of new car buyers roll debt from their old loans into a new one. That’s up from roughly 25% in the years before the financial crisis. The average amount rolled into the new loan is just over $5,000, according to Edmunds, an auto-industry research firm.

The primary driver of the increasing price of automobiles is improved safety features. The gorgeous cars of the 1950s would today be seen as flying coffins. Some of the money that Americans save by not winding up in the hospital after a car accident they must now pay up front when they buy a car.

Leasing, which often entails lower payments than purchase loans, accounted for 34% of financed new vehicles in the first quarter, up from 20% a decade earlier, according to Experian. Drivers of used cars also finance them—more than half did last year.

https://www.nbcnews.com/business/autos/new-car-safety-technology-saves-lives-can-double-cost-repairs-n925536

So, dent a fender or smack a mirror and you might need to repair or replace one of these sensors. AAA found that in a minor front or rear collision involving a car with ADAS technology the repair costs can run as high as $5,300. That’s about $3,000 more than repairing the same vehicle without the safety features.Subsequently, the chances of dying in an automobile accident continue to fall (even as Vehicle Miles Travelled has increased).

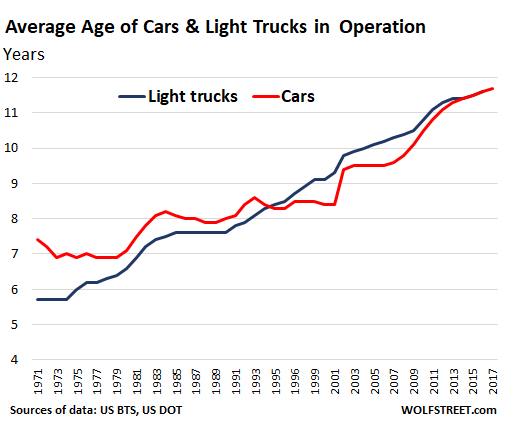

In a related development, automobiles are built to last much longer. The average lifespan of a car today is 12 years.

https://wolfstreet.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/US-auto-cars-trucks-average-age-2017.png

In the 1960s and ’70s, when odometers typically registered no more than 99,999 miles before returning to all zeros, the idea of keeping a car for more than 100,000 miles was the automotive equivalent of driving on thin ice. You could try it, but you’d better be prepared to swim.As with safety features, the increasing longevity of motor vehicles is partly a result of government regulation.

But today, as more owners drive their vehicles farther, some are learning that the imagined limits of vehicular endurance may not be real limits at all. Several factors have aligned to make pushing a car farther much more realistic.

Customer satisfaction surveys show cars having fewer and fewer problems with each passing year. Much of this improvement is a result of intense global competition — a carmaker simply can’t allow its products to leak oil, break down or wear out prematurely.

But another, less obvious factor has been the government-mandated push for lower emissions.

“The California Air Resources Board and the E.P.A. have been very focused on making sure that catalytic converters perform within 96 percent of their original capability at 100,000 miles,” said Jagadish Sorab, technical leader for engine design at Ford Motor. “Because of this, we needed to reduce the amount of oil being used by the engine to reduce the oil reaching the catalysts.

“Fifteen years ago, piston rings would show perhaps 50 microns of wear over the useful life of a vehicle,” Mr. Sorab said, referring to the engine part responsible for sealing combustion in the cylinder. “Today, it is less than 10 microns. As a benchmark, a human hair is 200 microns thick.

“Materials are much better,” Mr. Sorab continued. “We can use very durable, diamondlike carbon finishes to prevent wear. We have tested our newest breed of EcoBoost engines, in our F-150 pickup, for 250,000 miles. When we tear the engines down, we cannot see any evidence of wear.”Another reason for more durable cars is competition from Japan.

The trend toward better, longer-lasting cars seems to have begun way back in the ’60s, when the first imports from Asia started to encroach on American and European carmakers’ sales figures.

Another factor is that cars from the ’60s and ’70s were susceptible to rust and corrosion — many literally fell apart before their engines and transmission wore out. But advances in corrosion protection, some propelled by government requirements for anticorrosion warranties, have greatly reduced that problem.

“Competition is part of it,” said Peter Egan, a former auto mechanic and now editor at large of Road & Track magazine. “Japanese cars kind of upped everyone’s game a bit. With some exceptions, the engines would go a long time without burning oil or having other major problems.”

Hyundai and Kia, the South Korean carmakers, now include 100,000-mile/10-year warranties on their cars’ powertrains. If a relatively abusive driver can count on no major mechanical failures before 100,000 miles, a careful owner can — and does — expect his car to go much farther.In a sense, American cars slowly morphed into German cars -- more solid, more safe, more expensive. Americans, however, have not adopted German habits of automobile ownership. Germans buy cars with cash, not credit, and keep the car forever, replacing every part of a car until it essentially becomes a new car. The American mentality is rooted in the 1950s practice of trading in a car for a better car every few years, a practice based on two assumptions: 1) the income of the car owner will rise in the interval, and 2) a car is the equivalent of a disposable razor blade that needs to be swapped out.

Also, Americans generally don't buy cars. Seven of the top ten best-selling vehicles in the USA in 2018 were trucks and SUVs. While Americans swear that they need these big vehicles for practical reasons, these vehicles are actually much less practical.

https://www.foxnews.com/auto/the-10-best-selling-vehicles-in-the-united-states-in-2018-were-mostly-trucks-and-suvs

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/31/us/texas-truck-culture.html

In sum, automobile technology has changed, but Americans haven't.

College

New realities afflicted by old ways of thinking is also true in terms of the rising cost of college.Back in the 1950s, only about 5% of American adults completed college. That percentage now approaches 30%.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Educational_attainment_in_the_United_States

https://www.quora.com/What-is-a-gentleman%E2%80%99s-C

Given the decades-long history of grade inflation, particularly in Ivy League schools in the non-engineering disciplines, a “gentleman’s C” is proxy for “it should have been an F but we are too civilized to tarnish your record as such.”

In graduate schools this is perhaps even more pronounced.

I went to a top 30 or so law school where the grades were curved to a strict 3.17.

The saying there was “It’s hard to get an A; it’s even harder to get a C.” In practice the distribution was something like 15% As, 75% Bs, 10% Cs in each class.

I never heard of anyone actually failing, but it was well known that a C+ was the equivalent of a D, and a C- was tantamount to an F.This stands in contrast to those students who graduated from elite schools and who were not from the elite. The educational career of Robert McNamara is a case in point.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Robert McNamara was born in San Francisco, California.[3] His father was Robert James McNamara, sales manager of a wholesale shoe company, and his mother was Clara Nell (Strange) McNamara.[5][6][7] His father's family was Irish and, in about 1850, following the Great Irish Famine, had emigrated to the U.S., first to Massachusetts and later to California.[8] He graduated from Piedmont High School in Piedmont in 1933, where he was president of the Rigma Lions boys club[9] and earned the rank of Eagle Scout. McNamara attended the University of California, Berkeley and graduated in 1937 with a B.A. in economics with minors in mathematics and philosophy. He was a member of Phi Gamma Delta fraternity,[10] was elected to Phi Beta Kappa his sophomore year, and earned a varsity letter in crew. McNamara before commissioning into the Army Air Force, was a Cadet in the Golden Bear Battalion at U.C. Berkeley [11] McNamara was also a member of the UC Berkeley's Order of the Golden Bear which was a fellowship of students and leading faculty members formed to promote leadership within the student body. He then attended Harvard Business School, where he earned an M.B.A. in 1939.

Immediately thereafter, McNamara worked a year for the accounting firm Price Waterhouse in San Francisco. He returned to Harvard in August 1940 to teach accounting in the Business School and became the institution's highest paid and youngest assistant professor at that time.UC Berkeley charged no tuition up until Governor Ronald Reagan attempted to raise tuition in 1968. Berkeley might be understood to have been a free public school for the intellectual elite (like City College of New York) that has become a partly subsidized private elite university for the elites in general.

https://thebottomline.as.ucsb.edu/2017/10/a-brief-history-of-uc-tuition

It is often stated that there is a hierarchy of intellectual rigor in the university.

- STEM fields like math are the most difficult.

- The social sciences and humanities are not quite as hard.

- Business degrees are the easiest.

Rich students study general things; smart students study difficult things; everyone else learns a trade. The Bush dynasty is a case in point. President George W. Bush majored in history at Yale; his father, President George H.W. Bush, majored in economics at Yale; his father, Senator Prescott Bush, attended Yale (major unknown); his father, the industrialist Samuel Bush, attended Stevens Institute of Technology; his father, Rev. James Smith Bush, attended Yale; his father, Obadiah Bush, was a schoolteacher, prospector and abolitionist; his father, Timothy Bush, was blacksmith. As the Bushes moved up in the world, they went from the trades at the bottom to a generalized education for the aristocracy.

As more people go to college, this pattern might have become inverted.

In order to graduate from college, academically challenged students whose parents did not go to college gravitate to the social sciences and humanities, which have a reputation for being easy, "Mickey Mouse" majors. Ironically, this is the kind of academic career that once typified the aristocracy. One problem is that this liberal arts education for ordinary students is funded today by student loans, not by trust funds from Swiss bank accounts. Another problem is that unless one is going to Yale and one's father is President of the United States of America, such a degree is only really good for going to graduate school. Graduate school is perfectly fine for the likes of Robert McNamara, but does it really make sense for 90% of the population whose IQ is below 120?

In the meantime, the aristocracy has developed its own quasi-vocational career path that includes a traditional aristocratic education. In the UK, the PPE course of study is exemplary.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy,_politics_and_economics

Philosophy, politics and economics or politics, philosophy, and economics (PPE) is an interdisciplinary undergraduate/postgraduate degree which combines study from three disciplines.

The first institution to offer degrees in PPE was the University of Oxford in the 1920s. This particular course has produced a significant number of notable graduates such as Aung San Suu Kyi, Burmese politician, State Counsellor of Myanmar, Nobel Peace Prize winner; Princess Haya bint Hussein daughter of the late King Hussein of Jordan and wife of the ruler of Dubai; Christopher Hitchens, the British–American polemicist, [1][2] Oscar winning writer and director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck; Philippa Foot a British philosopher; Harold Wilson, Edward Heath and David Cameron, former Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom; Hugh Gaitskell, William Hague and Ed Miliband, former Leaders of the Opposition; former Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto and current Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan; and Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke and Tony Abbott, former Prime Ministers of Australia.[3][4] The course received fresh attention in 2017, when Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai earned a place.[5][6]

The PPE major is a weird hybrid in that it is modern vocational training for an established aristocracy.

In the 1980s, the University of York went on to establish its own PPE degree based upon the Oxford model; King's College London, the University of Warwick, the University of Manchester, and other British universities later followed. According to the BBC, the Oxford PPE "dominate[s] public life" (in the UK).[7] It is now offered at several other leading colleges and universities around the world. More recently Warwick University and King’s College added a new degree under the name of PPL (Politics, Philosophy and Law) with the aim to bring an alternative to the more classical PPE degrees.

Oxford PPE graduate Nick Cohen and former tutor Iain McLean consider the course's breadth important to its appeal, especially "because British society values generalists over specialists". Academic and Labour peer Maurice Glasman noted that "PPE combines the status of an elite university degree – PPE is the ultimate form of being good at school – with the stamp of a vocational course. It is perfect training for cabinet membership, and it gives you a view of life". However he also noted that it had an orientation towards consensus politics and technocracy.[4]

Geoffrey Evans, an Oxford fellow in politics and a senior tutor, critiques that the Oxford course's success and consequent over-demand is a self-perpetuating feature of those in front of and behind the scenes in national administration, in stating "all in all, it's how the class system works". In the current economic system he bemoans the unavoidable inequalities besetting admissions and thereby enviable recruitment prospects of successful graduates. The argument itself intended as a paternalistic ethical reflection on how governments and peoples can perpetuate social stratification.[7]

Stewart Wood, a former adviser to Ed Miliband who studied PPE at Oxford in the 1980s and taught politics there in the 1990s and 2000s, acknowledged that the programme has been slow to catch up with contemporary political developments, saying that "it does still feel like a course for people who are going to run the Raj in 1936... In the politics part of PPE, you can go three years without discussing a single contemporary public policy issue". He also stated that the structure of the course gave it a centrist bias, due to the range of material covered: "...most students think, mistakenly, that the only way to do it justice is to take a centre position".[4]To what extent is the quasi-vocational training of the elites a disaster? After the 2016 election, Barack Obama lectured Mark Zuckerberg on why Facebook's mission to "connect the world" and its policy to "move fast and break things" was maybe not such a good idea, yet Zuckerberg only came away confused. Focused on computer science, it is as though Zuckerberg never learned how to think while he was at Harvard.

Silicon Valley's Peter Thiel argues that college is obsolete and needs to be disrupted. The standard reply to Thiel is that the irrelevance of college only applies to a few Silicon Valley success stories like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Zuckerberg, men who dropped out of elite universities or prestigious colleges. But Zuckerberg's cluelessness is evidence that even though Thiel is wrong, the usual criticism of Thiel is even more wrongheaded. That is, future decision-makers in particular should be like Robert McNamara and be exposed to, fascinated by and engaged in the humanities. In fact, Steve Jobs would insist as much. (Jobs's great disappointment in life was dropping out of Reed College because he lacked the funds and the educational preparation because he was adopted by a working class family, as he angrily stated in his Stanford speech.)

The point is that in the past, very few people -- the aristocracy, men of talent -- went to college. The current assumption that everyone should to go to college is based on assuming what was once true for those few who did go to college will also apply to everyone.

- "Men of talent have rising incomes thanks to their college diplomas." This is a true statement.

- "The Aristocracy is generally not so talented, but they can handle college." This is likewise true.

- "The liberal arts are an excellent preparation for life." This is true for both the aristocracy and the Talented Tenth.

- "There is a correlation between a college degree and higher salaries." This is true for men of talent.

The thesis here is that everything has changed, but our way of thinking is stuck in the past. The irony is that the previous system of higher education might serve as a better model.

- Elite but easy education for the aristocracy, as long as they pay for it (Bushes);

- Elite, rigorous education for the Talented Tenth, free of cost (McNamara); and

- Vocational training for 90%, free of cost (although it might be called "college").

Houses

The rising cost of houses in the USA has many unexpected causes. Home sizes keep increasing, even while family sizes continue to decrease. Homeowners, many of them liberals, oppose upzoning their neighborhoods for higher density, which would lower home prices and make homes affordable for young families. Lonely seniors will not downsize and move out of their big houses, a lifestyle becoming popular among younger childless couples in the suburbs.One common theme on rising home prices is young Millennials conflicting with the older generation(s). The classic stereotype of Millennials is of the minimalist lifestyle: small, spare rented apartments in the city with few possession. However, studies show that Millennials somehow expect to someday own a house even larger than their parents' house.

As Albert Einstein said about nuclear war, everything has changed except the way we think.

Medical care

The only things I know about healthcare policy are from reading articles by the surgeon Atul Gawande.https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/atul-gawande

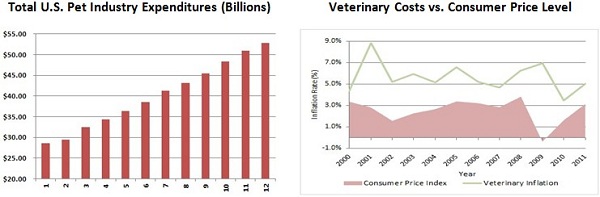

However, I do know a little about healthcare spending on pets. During the worst days of the 2009 recession, spending on all things fell except for two categories: vitamins and pets. People ate less food and ate cheap food, and supplemented their diets with vitamins. They reexamined their lives and concluded that the best thing in their lives was their pet, and so they spent more on pet food and veterinary care.

This is a "crisis trend", in which a trend is exposed and accelerated by crises like war and recession.

Let's contrast this with the past, specifically with the BBC classic "All Creatures Great and Small" about a veterinary clinic in rural northern England.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_Creatures_Great_and_Small_(TV_series)

The primary job of veterinarians used to be to help large farm animals like cows and horses give birth. The primary tool of the trade was a stethoscope.

Today, dogs and cats are primarily companion animals, and as members of the family, people are willing to spend large amounts of money on them. The tools of the trade now include MRIs, insulin shots and stem cell therapy.

We talk about the "rising cost of technology", but technology drives costs down over time. What rises are expectations. People import expectations from their knowledge of human life spans and human medical technology and apply that to their pets. The lifespan of a serious working dog might be five years (which is the typical lifespan of a wolf in the wild). As a pet, a dog might now live 12 years (the lifespan of a wolf in captivity), but people assume that there is something wrong with this, this is too short a period. So while the technology of veterinary technology has transformed, people have unrealistic expectations based on earlier ways of thinking (about humans).

Trends versus predictions

The forecasts of preeminent economists feel a bit like fortune-telling. The fortune teller will amaze the customer with insider knowledge and then make a very specific prediction about exactly what will happen in the future and precisely when it will happen.The insider knowledge consist of processes and trends that no one else is observing. Out come the charts about previous downturns and statistics that everyone else has forgotten about. It seems plausible and illuminating.

The predictions have an odd certainty. These two countries will go to war and interest rates will go down by so many points. After so many months, the credit bubble will then burst.

It seems difficult enough to observe or at least try to apprehend trends without making predictions.

One general trend now is for the USA to move away finally from global leadership with the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War almost three decades ago. "America First" isolationism might not have been inevitable, but the old role of global policeman began to ring hollow over a generation. In this situation, one would expect increasingly open conflict between American allies like Japan and South Korea, and regional trade conflicts would ensue. So the collapse of free trade might be much worse than Roubini expects from the current tariff spats between the USA and China.