A report states that Airbnb is reducing the availability of rental housing and driving up the price of rentals in New York City.

https://www.usnews.com/news/business/articles/2018-01-30/report-slams-airbnb-in-nyc-for-raising-cost-of-housing

The analysis published Monday comes from a researcher at McGill University in Montreal and was commissioned by the Hotel Trades Council, a hotel worker union. Several local neighborhood organizations were co-sponsors.

The report finds that Airbnb listings have removed between 7,000 and 13,500 housing units from circulation in the past three years and increased the city's median rent by $380 a year. In Manhattan, Airbnb listings have driven up the median annual rent by $780, according to the report.

Airbnb countered with its own statistics, arguing that Airbnb rentals in NYC last year served 2 million guests and generated $3.5 billion in economic activity.

More criticism of Airbnb:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/03/nyregion/airbnb-rent-manhattan-brooklyn.html

Airbnb’s growing influence caused rents to increase significantly in tourist areas and gentrifying neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where the majority of the company’s rentals are concentrated, according to a report released on Thursday by the city comptroller’s office.

In Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen and Chelsea neighborhoods and the Midtown Business District, which accounted for about 11 percent of all Airbnb listings in New York City in 2016, average monthly rents increased by $398 between 2009 and 2016, of which $86, or 21.6 percent, was a result of Airbnb’s presence, the report said. In Greenpoint and Williamsburg in Brooklyn, the study said, rents went up 18.6 percent in those years because of Airbnb listings.

In the first instance, about 20% of rent increases in a seven-year period in NYC were due to Airbnb short-term rentals. In the second instance, rents increased by about 20% due to Airbnb.

The rent increases due to Airbnb are largely limited to Manhattan and Brooklyn.

The comptroller’s report shed light on the clash of the so-called sharing economy with city neighborhoods struggling to preserve their stock of affordable housing and rein in skyrocketing rents, though the report also found that the online rental site had a negligible effect on most neighborhoods outside of Manhattan and Brooklyn, where listings are sparse.

It seems that it is in the touristy parts of NYC that Airbnb has an impact on rents.

The report had limitations. The report failed to comprehend that there is not necessarily a trade off between long-term and short-term rentals.

An apartment listed on Airbnb does not always translate into a unit lost in the long-term rental market, because apartments may be rented for a short amount of time a year.

This is especially true in New York City. This is because one historical aspect of life in NYC is that New Yorkers have always tended to be people who spend weeks away from home. Short-term rentals were always an aspect of life in NYC long before Airbnb emerged, and such short-term rentals do not necessarily displace long-term rentals.

Airbnb objected to the reports findings.

Mr. Kalloch said Airbnb’s effect on rents was insignificant because listings represent less than 1 percent of apartments in the city. But he acknowledged that some neighborhoods have a significantly higher share of Airbnb rentals. He also said that using 2009 as a starting point distorts the findings because rents in New York tanked during the Great Recession that year.

Most New Yorkers, Mr. Kalloch said, use Airbnb as a source of extra income to make ends meet and that entire apartments are rented for a median of 60 nights a year.

More research on Airbnb in NYC.

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/03/what-airbnb-did-to-new-york-city/552749/

Wachsmuth found reason to believe that Airbnb has indeed raised rents, removed housing from the rental market, and fueled gentrification—at least in New York City. To figure out how, the researchers mapped out four key categories of Airbnb’s impact in New York: where Airbnb is concentrated and how that’s changing; which hosts make the most money; whether it’s driving gentrification in the city; and how much housing it has removed from the rental market.

Over 10% of Airbnb operators are essentially commercial operators who

skip paying the taxes that hotels pay.

While many people still use the platform this way, Wachsmuth found that 12 percent of Airbnb hosts in New York City, or 6,200 of the city’s 50,500 total hosts, are commercial operators—that is, they have multiple entire-home listings, or control many private rooms. And these commercial operators earned 28 percent of New York’s Airbnb revenue (that’s $184 million out of $657 million).

Like hotel managers, these hosts tend to be market-savvy: They often charge less per night than other hosts do and adjust their rates to attract a high number of rentals overall. Unlike hotels, they don’t pay commercial property taxes or hotel taxes. And that’s a problem, both for the city itself and for other hosts.

This inspires a thought:

Perhaps all short-term rentals should pay hotel tax and commercial property tax.

Airbnb is not really "home sharing". (Home sharing is when relatives and friends spend the weekend for free.) Airbnb is really an online platform that lists short-term home rentals for leisure travelers. Notably, Airbnb is now on the cusp of directly competing with the hotel industry for mainstream customers (businessmen).

In particular, "commercial" short-term rentals -- in which a land owner rents out multiple homes -- are perceived as competition by the hotel industry. Moreover, the competition posed by commercial home renters impacts non-commercial hosts who rent short-term. Such commercial multi-home rentals are also illegal.

If this sound illegal, that’s because it is. It contradicts Airbnb’s “one host, one home” policy, which was introduced in New York City in 2016. That policy limits New York-area hosts from listing rentals at more than one address. It also violates New York State’s Multiple Dwelling Law (MDL), which forbids short-term rentals of fewer than 30 days in buildings with three or more units, unless the owner is present. While it is certainly possible for a host to have multiple legal listings that all refer to the same property, using American Community Survey data from 2011 to 2015, the researchers calculated that anywhere between between 42 percent and 46 percent of all active listings have had illegal reservations.

New York’s MDL, which has been in effect in some iteration since 1929, is difficult to enforce. In a situation where the law tries to go after someone, Wachsmuth said “the landlord can say, ‘Oh, I was there—I was just in a different room.’ They can’t prove that they weren’t.”

(Again, perhaps having all hosts pay hotel and commercial property tax might help to fix that enforcement problem.)

There tends to be a relatively small number of Airbnb hosts (10%) who are making a big chunk of the profits (almost half).

Overall, his data suggests that half of all Airbnb rentals that are conducted by only 10 percent of hosts, who earned a full 48 percent of all the revenue earned in the city last year. That’s some 5,000-people earning a combined $318 million. In contrast, the bottom 80 percent of New York’s hosts—the city’s 40,400 true home sharers—earned just 32 percent of all revenue, or $209 million, in 2017.

The top 10% of hosts who are raking in almost 50% of total Airbnb revenue are probably commercial operators renting out multiple properties, and not rooms in the homes that they live in. Moreover, they are probably renting out on a short-term basis throughout the entire year, precluding the possibility of long-term rentals.

To be fair, this might be true of all enterprises. It reflects the Pareto principle or 80/20 rule. The scholar Vilfredo Pareto noticed that 20% of landowners in Italy owned 80% of the land, a pattern that he began to find throughout his economic research. That is, this kind of disproportional profiting is typical of all markets. It could be argued that it is normal and natural. It could even be argued that it is a healthy hallmark of the entrepreneurial spirit. (The issue then would be whether the top 10% of owners accruing 50% of revenues are paying 50% of the taxes.)

Nevertheless, hosts who play by the rules earn less than illegal commercial operations. That is unfair.

But there is a bigger problem here -- and a bitter irony.

By renting out their homes in order to survive economically, hosts are driving up the cost of living for themselves and everyone else. This smacks of the Tragedy of the Commons.

In other words, using Airbnb to help pay your bills in a space-strapped city is a bit like using an air conditioner to combat global warming: It might help keep your apartment bearable, but overall it’s just making the environment worse.

There is yet another bitter irony.

Some Airbnb rentals can be compared to "flophouses" or

SROs --

Single Room Occupancy hotels.

SROs -- also once known as "boarding houses" -- provided so much of the housing for immigrants and workers a century ago.

The difference between boarding houses and Airbnb is that Airbnb rentals are aimed at short-term rentals to

tourists, not locals, driving up the cost of rent.

In this way, Airbnb is even worse than the lamented flophouse. At least the flophouses and boarding houses provided a place to live for the lower classes.

Moreover, Airbnb abusers manage to skirt regulation as unlisted "ghost hotels".

Wachsmuth compares Airbnb ghost hotels to flophouses—single-room occupancy hotels popular in American cities like New York and San Francisco in the early 20th century. (Here’s an amazing visual history of SROs from CityLab visual storyteller Ariel Aberg-Riger.) However, while flophouses often provided housing for all manner of city folk—such as immigrants, factory workers, and minority groups—ghost hotels largely cater to tourists. And because the hosts that run them are renting out individual rooms rather than whole homes, it can be easier for them to avoid municipal regulation, too.

“What’s interesting is that this kind of activity has a long history in New York,” he said. “I’m not aware of other jurisdictions where there’s almost 100 years of grappling with short-term rentals.”

Interestingly, it has been asserted that "co-living" or "dormitories for adults" that appeal to young adult Millennials living in the city are really just a resurrection of SROs. That is, boarding houses have re-emerged for a new demographic.

Interestingly, the history of SROs in NYC is a microcosm the major changes on that city in the past century.

At one time in NYC, most of the housing stock consisted of SROs that were known as "boarding houses" that existed for workers and immigrants. With the rise of suburbs and the deinstitutionalization of mental institutions, SROs became known as "flophouses" and were associated with the permanently down and out. Today, SROs in the city are known as "co-living" dormitories for Millennials.

https://www.curbed.com/2018/3/8/17097154/affordable-housing-coliving-starcity-common-sro

The connection between Airbnb and SROs may yet prove to be important. But so far, few have remarked on the potential evolution of Airbnb into an SRO management service. Instead, there are proposals to regulate Airbnb.

To solve the abuse of short-term rentals, the author of the study (Wachsmuth) recommends a three-step approach.

- Enforce the "one host, one home" policy.

- Legalize rentals that are shorter than 30 days (as a compromise).

- Eliminate full-time rentals.

Unfortunately, these recommendations seem to miss the point. These recommendations are both too restrictive and not radical enough.

That is, these recommendations seem somewhat arbitrary in the face of the greater truth -- that Airbnb has become a hotel chain.

Perhaps short-term rentals should simply be treated for what they are -- hotels -- and regulated as such.

Here is an editorial that agrees with this:

https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-04-17/airbnb-plays-a-minuscule-role-in-rising-city-rents

Another issue is that criticisms of Airbnb are typically not very clear on the impacts of Airbnb on rents and home prices.

Rent increases due to Airbnb are to be expected. This is because any increase in short-term rentals would logically lead to a decline in supply for long-term rentals, driving up rental prices.

The question is by how much.

The actual impact on rent by Airbnb is negligible.

As evidence that Airbnb is actually driving rent increases, Wachsmuth cites a very recent paper by economists Kyle Barron, Edward Kung and Davide Proserpio. Barron et al. reason that if a given area is a big draw for tourists, with lots of eating and drinking places, and that if that area receives a sudden surge in online search interest for Airbnb, then any subsequent jump in Airbnb is caused by increased demand from visitors for short-term rentals.

Under this assumption, Barron et al. find that the true impact of Airbnb on rents is very small. A 1 percent increase in Airbnb listings, they found, raises rents by only 0.018 percent. That’s a minuscule effect. It means that doubling the number of Airbnb listings would raise rent by less than 2 percent overall. The effect is so small that in their presentation at the American Economic Association meeting in January, the authors referred to it as a “zero effect on rental rates” overall (though the effect isn’t necessarily zero in all areas).

The minuscule impact that Airbnb has on rents has policy implications.

This means that the advent of Airbnb probably doesn’t require much of a policy change. Its small impact can easily be canceled out by simply building a bit more housing. Tokyo itself has done this, with great success.

But that’s not quite the end of the story. Barron et al. also find that one reason Airbnb’s impact is so small is that most people offering rentals are owner-occupiers sharing their own residences, rather than commercial operators operating fly-by-night mini-hotels. If cities allow the latter, the effect on rents will probably be bigger.

One approach is to do what New York has done, and simply ban commercial Airbnb operators. But, given the benefits for travelers, a smarter approach might be to allow commercial Airbnb operation but to tax and regulate it like the hotel industry. Buildings that allow commercial Airbnb operations could be required to advertise this fact to potential tenants, and commercial Airbnb operators could be required to follow cleaning and safety procedures similar to those used by bed and breakfasts. Finally, a tax could be applied to commercial Airbnb operation, with the proceeds used to fund affordable housing.

Earlier studies quoted above claimed that Airbnb's presence led to a 20% increase in rents or comprised 20% of rent increases.

First, that was from 2009 to 2016, when real estate markets were recovering from the Great Recession. The traveling public was willing to pay a premium for short-term home rentals in the face of a still-low supply of hotels and houses.

Second, that was in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where demand for Airbnb is stronger than perhaps anyplace else in the USA. The time and place of these 20% figures are unique.

Also, even the 20% figures are not very high.

The concern with Airbnb as a source of rising rents and higher home prices seems unusual in terms of the contemporary issues in urban development.

For the past ten years, the standard narratives found in the mainstream media on the issue of the affordability of homes in 21st-century America do not mention short-term home rentals at all.

In this context, the demonization of Airbnb seems to emerge out of nowhere.

Here are some the reasons typically given to explain why home ownership is often out of reach.

- In the 21st century, educated young creatives, professionals and corporate executives are moving into the urban core, driving up urban land prices and compelling the less advantaged to move from the cities into the suburbs (where there are fewer social services). This reverses the great exodus of the rich and middle class into the suburbs that took place during the latter half of the 20th century.

- Home building was profoundly interrupted by the 2009 recession.

- Increasing levels of student debt are delaying home purchases.

- Cities are typically built adjacent to major bodies of water. Consequently, many cities are hemmed in by water, precluding the possibility of building outward.

- Established homeowners intensely resist further development, and especially oppose rezoning for higher density (taller buildings).

- Luxury houses and condominiums, so often bought on spec, are so often empty all year round, driving up rents and home prices.

- Americans are loath to fund public or affordable housing (in contrast, under the British, half the homes in Hong Kong consisted of public housing, despite Hong Kong's extreme laissez-faire economic policy).

- English-speaking countries, especially the United States, exhibit a disdain for urban life, with a preference for houses in the suburbs over apartments in the city, a bias that drives up home prices.

All of the above militate against the creation of further housing supply.

If short-term rentals are not really the problem in the unaffordablity of rent and unattainability of home ownership, why the apparent scapegoating of Airbnb?

What might be going on is opposition by the hotel industry, which would be somewhat affected by short-term rentals to tourists and very affected by rentals to businessmen.

Also, politicians have a convenient scapegoat in the figure of Airbnb. All the real issues surrounding unaffordability are too complicated and intractable to address publicly.

Moreover, people fear change. Airbnb is something new and unfamiliar that grew very rapidly, while most of the other issues listed above have been around a long time.

Has the hotel industry in fact been disrupted by Airbnb? No, not yet.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2018/02/airbnb-hotels-disruption/553556/

Five years ago, the Disrupt Story went that Airbnb was going to challenge hoteliers and maybe even make their business obsolete, as young people ditched Marriotts and Hiltons for the empty beds of strangers.

So, naturally, the hotel business is in a state of wretched suffering—yes?

Quite the opposite.

Last year was the best year ever for hotel occupancy in the United States. The stock prices for the major hoteliers Marriott and Hilton are both up more than 40 percent in the last 12 months.

Airbnb fits the classic model of "disruptive innovation" in its first stage.

The Harvard professor of business Clayton Christensen theorized that the classic disruptive product finds a niche on the margins of the marketplace as an inferior but cheap and convenient alternative that appeals to outliers, but has no appeal to the mainstream customer. In the second phase of disruptive innovation, the product's quality improves over time and its popularity sweeps through the mainstream, and the product becomes dominant.

Airbnb's appeal has been for the young leisure traveler looking for a vacation rental, not the serious business traveler who is the mainstay of the hotel industry.

Let’s review what the market for accommodations looked like before Airbnb came along. Most vacation rentals were in empty second homes, often in beach, resort, and ski towns; renting them meant knowing an owner personally or working through a local agency. Meanwhile, most brand-name hotels in major U.S. cities were (and still are) near business centers, where locals might work, but rarely sleep, wake, and wander around.

Airbnb’s great contribution was to allow travelers to live as locals do—in the busy downtown residential areas, near the best restaurants, bars, and other local hangouts. Business travelers might prefer the amenities of a hotel. But what Airbnb offered was a superior simulacra of the local experience for leisure travelers—for an affordable price, which happened to support some local dwellers’ income.

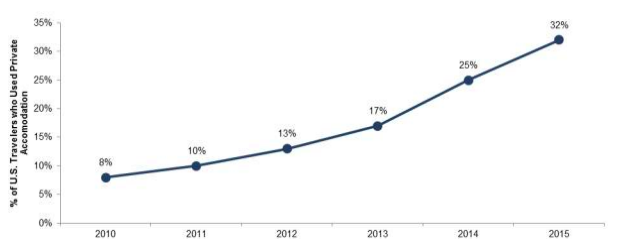

Airbnb’s business took off among a particular demographic—young, urban, and relatively well off. Half of Airbnb’s bookings are made by Millennials, or those under 35 years old, and most of them are for leisure rather than business, according to the research firm MoffettNathanson. Airbnb has left an impressive mark on the way people travel to big cities: The share of American travelers using “private accommodations” like Airbnb quadrupled between 2010 and 2015, according to MoffettNathanson.

Airbnb's stunning growth has not hurt hotels because hotels have a different clientele. However, some business travelers did opt for Airbnb in the post-recession hotel-room shortage, which helped to keep hotel rates down.

First,

business travelers still prefer hotels; more than 90 percent of Airbnb’s business is in personal tourism. Second, if it weren’t for Airbnb, travelers might be suffering through a terrible squeeze in hotel space. The construction pipeline of new hotels

plunged after the Great Recession. As the economy recovered and travel picked up, it seemed inevitable that the prices of scarce hotel rooms in major U.S. cities were set to soar. But they didn’t. Airbnb-listed rooms vastly expanded the supply of beds for travelers—tourists and business travelers alike—to lie in. With the explosion of the private accommodations market, rooms opened up and hotel prices stayed

down.

However, Airbnb is now moving into the hotel business.

This might signify the beginning of the second stage of disruptive innovation, when the incumbent industry is swept aside for the new model.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/enriquedans/2018/02/24/airbnb-squares-up-to-fight-traditional-hotels-on-their-own-turf/#21d493737145

Interestingly, in none of these articles is there mention of movement in the other direction --

turning hotels into homes.

This would be

hotel to condo conversion. In the 2000s, it was often mentioned as a big trend. Some of the hotel rooms converted to condominiums might be expected to eventually rented out via Airbnb, effectively becoming hotel rooms again.

This highlights another point.

The hotel industry is not synonymous with the tourism industry. The hotel industry might get disrupted, but

this might actually stimulate tourism.

Unfortunately, Airbnb might do too good a job at promoting tourism.

This is the problem of "

overtourism", according to the New York Times' Farhad Manjoo. Travel destinations have become saturated with tourists thanks to a super-connected world.

If travel mishaps are the stuff of memory, my vacation was unforgettable. And without home-sharing services like Airbnb, review sites like TripAdvisor and conveniences like Uber, OpenTable and Expedia, the trip would have been far more expensive, less accessible and, in a strange way, less authentic.

But my tech-abetted trip was illuminating, too, because it provided a firsthand look into a vexing problem that has gripped much of Europe lately — the worry of “overtourism,” and the rising chorus that blames technologies like Airbnb, Uber and other internet-enabled travel conveniences for the menace.

As the world develops and populations become more affluent, the number of tourists around the world keeps increasing. This has strained the resources of the tourist industry and altered the character of historic cities, making tourism somewhat pointless.

The technological innovations of the past generation have played an essential role in this transformation.

Over the last few decades, innovations in aviation — wider, more efficient jets and the rise of low-cost airlines — significantly reduced the cost of flying. Bigger cruise ships capable of holding many thousands of passengers now take entire floating cities to coastal ports (which is why Venice recently banned these). Then there are the many splendors enabled by the internet, among them online booking, local reviews, smartphone mapping, and ride-hailing and home-sharing, which have collectively democratized pretty much every step involved in travel.

People used to spend big money on big cars and big houses in order to get big attention.

Nowadays, people spend big money on big vacations so they can build a big reputation on social media.

It is often said that young Millennials are more interested in having experiences rather than owning things. Actually, just like their parents and grandparents, they are obsessed with investing heavily in their public image. The only difference is that the image is now online.

“You can’t talk about overtourism without mentioning Instagram and Facebook — I think they’re big drivers of this trend,” Mr. Francis said. “Seventy-five years ago, tourism was about experience-seeking. Now it’s about using photography and social media to build a personal brand. In a sense, for a lot of people, the photos you take on a trip become more important than the experience.”

Airbnb in particular has been targeted for regulation.

That brings us to the hand-wringing over Airbnb, which has been singled out by lawmakers across Europe as a primary driver of overtourism. In Amsterdam, the authorities are pushing to slash the number of nights that residents can rent their homes to 30 from 60. Several other cities, including London and Barcelona, Spain, have also instituted stringent home-sharing rules.

The measures reflect Airbnb’s jaw-dropping growth. In just a few years, the company has become a significant force in the tourism economies of many cities. In Amsterdam, according to the company, Airbnb accounted for 12 percent of all overnight bookings in 2017. In Barcelona, Airbnb had an 18 percent market share. And in Kyoto, Japan, it was 22 percent.

In the "big picture" view, however, Airbnb is really just a symptom of something greater. The real issue is modern tourism itself.

“At the end, this story is just a numbers problem,” Mr. Tourtellot said. He noted that in 1960, when the jet age began, around 25 million international trips were taken. Last year, the number was 1.3 billion.

As for the cities that are the major destinations? They are “the same size they were back in 1959, and they’ll probably stay that way,” he said.

But tourism -- and Airbnb -- can be a salvation as well.

To some extent, Airbnb has helped to relieve a country like Japan from the economic stagnation that has afflicted it for a generation. Japan was once famous for exporting its tourists, and now it eagerly imports tourists. Without the need to build new infrastructure such as hotels, short-term home-renting has allowed Japan to host more tourists.

At least Airbnb generates economic activity. What is truly disturbing is condominiums and houses that become permanently empty after they are purchased as investments (often by wealthy foreigners).

This might be the bigger problem in the world of rising rents -- empty houses and apartments purchased as investments.

Unfortunately, the same politicians who express the concerns of the hotel industry by scapegoating Airbnb are also very attuned to the interest of land developers and the real estate industry. These politicians rationalize how empty luxury houses and empty luxury condos are good for the economy because they bring in property tax. While it might be true that empty homes do generate tax revenue without straining infrastructure, these empty properties might have a greater impact on rent and real estate prices than do short-term rentals.

Interestingly, the purchasing of homes by foreigners can also become a form of scapegoating. For example, in August 2018 New Zealand's banned the purchase by foreigners of existing homes in order to lower the price of homes. Housing prices in Auckland have doubled in the past decade and have risen 60% nationwide, and foreign home buyers make for a convenient scapegoat.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-newzealand-politics-housing/new-zealand-passes-ban-on-foreign-homebuyers-into-law-idUSKBN1L00KO

One problem with a ban on the foreign purchase of homes is that so much of the new construction which will eventually provide homes for locals is driven by outside investment.

The government slightly relaxed the proposed ban in June so that non-residents could still own up to 60 percent of units in large, newly built apartment buildings but would no longer be able to buy existing homes.

The International Monetary Fund called on the government in July to reconsider the ban, warning the move could discourage foreign direct investment necessary to build new homes.

“Foreign buying ... tends to be focused on new development, making clear again that foreign investment leads to the creation of new dwellings. That’s vital in a market with a housing shortage, like Auckland,” he said.

Like the controversy over Airbnb, the factual evidence does not clearly justify the public outcry against foreign purchases of homes in New Zealand.

Official figures suggest that the overall level of foreign home buying was relatively low - about 3 percent of property transfers nationwide.

However, the data did not capture property bought through trusts and also showed property transfers involving foreigners was highly concentrated in certain areas, such as downtown Auckland and the southern scenic hot spot of Queenstown.

Banning the purchase of

existing homes does show some sensitivity to the law of supply and demand in that it allows for the construction of new supply. Perhaps it would be even better if the law went further and

mandated that every house be occupied.

Airbnb, Uber and "displacement innovation"

Airbnb fits the classic model of "disruptive innovation", in which a cheaper, inferior product finds a niche at the margins, improves over time and then sweeps through and comes to dominate the mainstream market. Airbnb's origin was basically as a low-end, make-shift vacation-house referral service.

Uber's development was not classic "disruptive innovation" like Airbnb's.

Uber fits the model of "sustaining innovation" in which a good product becomes better -- although, paradoxically, Uber started at the high end of the market and worked downward. Uber was originally a luxury driving service that subcontracted and developed an app for faster service. In doing this, Uber essentially became a high-tech taxi company that expanded the customer base of taxis by appealing to people who typically could not afford a taxi. What might be called a "downmarket sustaining innovation" -- in which quality improves even while prices are driven down -- might be as lethal to the competition as classic disruptive innovation. (SpaceX is likewise a "downmarket sustaining innovation" in which a mainstream product has improved over time but -- counter-intuitively -- has moved downmarket in terms of costs.)

https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/12/02/fresh-insights-from-clayton-christensen-on-disruptive-innovation/#57bff0734702

Airbnb is a classic case of disruptive innovation. They started out at the low-end—targeting customers who couldn’t afford a hotel (or who couldn’t book one in a crowded market). It was a pretty crummy alternative to hotels. But over time, they have moved upmarket—going after nicer and nicer homes in wealthier areas.

Uber [is] a sustaining innovation vis-à-vis taxis, not as a disruptive innovation, because Uber doesn’t operate at the low-end foothold or a new market foothold as specified by the theory of disruptive innovation.

There is a semantic problem here. The term "disruption" as Harvard professor Clayton Christensen intended it is a technical term used to describe a specific technological-economic process of market transformation. This meaning is quite different from the everyday sense of the word "disruption".

But when I talk to taxi drivers, most of whom don’t read Harvard Business Review, they tell me, “Uber is really disrupting my business.” They are using “disrupt” in the sense of the plain English word “disrupt”. What then should we call what is happening in the market being served by taxis and Uber? Is it wrong to call it disruption? Should we tell the taxi drivers that they are not being disrupted after all, and that the industry is actually being sustained, not disrupted? Is that plausible, just as a matter of English language?

A better term for "

disruptive innovation" might be "

market-displacement innovation" because it is not just a particular company or product that is surpassing another in popularity, but an entirely different market that is overwhelming and displacing another, unrelated market. For example, the smartphone as a convenient portable internet device displaced much of the mainstream market for laptop computers (which are technologically far superior to smartphones). Steve Job's philosophy was that Apple should not be afraid to cannibalize its own established products with new products, a strategy which goes against human instinct as well as conventional business sense, but which makes Apple less vulnerable to market displacement. But it was not just a product that was being displaced when the iPhone displaced laptops, but an entire category of technology.

Another semantic flaw can be found in the narrative of how market-displacement innovation happens: An inferior product finds a niche in the fringes, improves over time and then sweeps upward to capture the mainstream market. The "fringes" in the case of market-displacement innovation refer to

a completely distinct market from the mainstream market, and

not to the lower end of the mainstream market. An example of the lower end of the mainstream would be found in discount clothing, which recently improved over time and moved up to take on the apparel business; but this is really a case of sustaining innovation, where a product (cheap clothing) that was always really part of the mainstream market got better.

In contrast, Airbnb is a potential market-displacement innovation in relation to the hotel industry because Airbnb was originally a totally different market from hotels -- off-brand vacation rentals.. Back then, Airbnb appealed to a certain class of tourist -- "bobos", or bourgeois bohemians -- who would never stay in a hotel because they preferred something less generic. Later, as business travelers found it necessary to sometimes engage in the short-term renting of homes in the face of the post-recession hotel crunch, the online vacation rental market (Airbnb) absorbed some of the spillover of the customer base of the mainstream market of hotels -- without displacing the hotel market. But the online short-term home-rental market -- once a fringe market dedicated to an eccentric brand of leisure traveler -- has since professionalized, and is now poised to conquer and vanquish the hotel market for business travelers.

An analogy to market-displacement innovation might found in diseases that exclusively infect certain species -- birds, for example. The disease may grow more and more virulent without affecting other species. Suddenly, the disease crosses the species barrier and infects humans. To paraphrase Monty Python, nobody expects the bird flu. Likewise, nobody expects displacement by an entirely different market (and an inferior market at that). The displacement of one market by another is not only typically unexpected, but even when incumbents do clearly foresee the coming apocalypse of their market, they so often become paralyzed instead of responding vigorously (e.g., Kodak's halting response to the rise of the digital camera market despite Kodak seeing the threat well in advance and taking it very seriously).

Christensen notes that his original theory was originally published in the Harvard Business Review in 1995.

Since then, the term "disruption" has become extremely popular but misunderstood in terms of how Christensen meant it -- much the way terms like "paradigm shift" and "deconstruction" were widely misused even within the academic world that propagated them.

Not only is Christensen's theory still poorly understood, but it has continued to evolve over time, unbeknownst to the public and academia.

Christensen now recognizes

three types of innovation. (Here he describes them in terms of economic growth and job creation.)

In the first case, a once-inferior off-brand market (like Airbnb) displaces the mainstream market.

One type of innovation are [disruptive or] market-creating innovations, which are disruptive in the [proper] sense. These are innovations which transform products that are complicated and expensive into things that are so much more affordable and accessible that many more people are able to buy and use the product. You have to hire more people to make it and distribute it, sell it and service it. This is where growth comes from.

In the second case, within a particular market, a new and superior product (like Uber) succeeds an older, outdated product.

The second type of innovation are sustaining innovations. Their role in the economy is to make good products better. They are very important in the economy, because sustaining innovations keep margins attractive and they keep the market competitive and vibrant. They can improve profitability, and create some top-line growth through price increases, but they typically don’t create growth from new consumption, nor do they generally create jobs.

This was a surprise to me. Just imagine if I am a sales guy and I convince you to buy the Toyota Prius, the hybrid car. If I succeed in selling you that, you won’t buy a Toyota Camry. If I sell you the new version of the product, you won’t buy the old version of the product. So by their very nature, sustaining innovations replace other products and so don’t create aggregate new growth.

In the third case, a commodity can be produced more efficiently over time, reducing employment.

The third type of innovation, which we missed in earlier versions of disruption theory, concerns efficiency innovations. The purpose of efficiency innovations is to do more with less. This includes some of the innovations that have followed disruptive pathways to mainstream dominance. From a competitive point of view, they have the same impact, and incumbents can be eliminated. But their purpose in the marketplace is to increase efficiency. For example Walmart, had the effect on department stores of disruption because those stores weren’t able to respond. But from a growth point of view, they made retail much more efficient and resulted in net fewer jobs. And in the steel industry, mini-mills don’t create new growth, because they are an efficiency innovation.

Walmart represented a "market-creating innovation" or "displacement innovation" in terms of a "big box" store undermining established department stores.

Walmart could also be seen as a "downmarket sustaining innovation" in relation to the small, independent, family-owned, non-franchised "mom-and-pop" general stores and drug stores that it underpriced and also outperformed in terms of having a centralized location for "one-stop shopping".

But as an "efficiency innovation", Walmart is still basically an old mom-and-pop store that has paradoxically attained monstrous hyper-efficiency through sheer systematic frugality (Sam Walton's obsession).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walmart#1945%E2%80%931969:_Early_history

In 1945, businessman and former J. C. Penney employee Sam Walton bought a branch of the Ben Franklin stores from the Butler Brothers. His primary focus was selling products at low prices to get higher-volume sales at a lower profit margin, portraying it as a crusade for the consumer. He experienced setbacks because the lease price and branch purchase were unusually high, but he was able to find lower-cost suppliers than those used by other stores and was consequently able to undercut his competitors on pricing. Sales increased 45% in his first year of ownership to US$105,000 in revenue, which increased to $140,000 the next year and $175,000 the year after that. Within the fifth year, the store was generating $250,000 in revenue. When the lease for the location expired, Walton was unable to reach an agreement for renewal, so he opened up a new store at 105 N. Main Street in Bentonville, naming it "Walton's Five and Dime". That store is now the Walmart Museum.

The case of Walmart raises an interesting question....

Can a product or technology exhibit more than one of these three types of innovation?

For example, the

smartphone is a

market-displacing innovation in relation to laptops in the market of computers, but it represents

sustaining innovation in relation to landline phones and basic cell phones within the telephony market. Moreover, smartphones are an

efficiency innovation, not so much in relation to basic cell phones (which are simpler than smartphones to use

as telephones), but in terms of so many other activities, especially work related (e.g., Siri, the simulated office assistant on the iPhone). So perhaps a product or technology could embody different kinds of innovation in different markets.

Perhaps even

Apple Inc. likewise manifests all three kinds of innovation. After all, Christensen has pointed out that it is not just a technology or a product that is market-displacing, but a business plan.

Apple was originally a computer company when it was incorporated in 1977 as "Apple Computer, Inc." Twenty years later, when the iPhone came out, Apple reincorporated as "Apple, Inc.", with a clarified focus on consumer electronics. This is as if Dell had transformed itself into The Sharper Image. In fact, The Sharper Image went bankrupt in 2008, perhaps largely because Apple eclipsed its market; so many of the futuristic products in a Sharper Image store -- fancy clock radios, gimmicky landline telephones -- were rendered obsolete by the smartphone (which was essentially a computer disguised as a telephone). A struggling, marginal computer maker improved its product and moved into an entirely different market and decimated it -- along with so many other markets (for example, wristwatches). This is

market-displacement innovation.

However, Apple still makes personal computers. In fact, within its original market of personal computing, Apple's computers are often considered to be the most advanced. This is

sustaining innovation.

Moreover, Apple's products have transformed so many segments of work life (e.g., airline pilots and navigators utilizing iPads instead of paper maps). This is

efficiency innovation.

Products or technologies that manifest all three types of innovation might be termed "

trifecta innovations". A trifecta innovation would be deadly to its competition and entail all kinds of societal transformation. It might also become a monopoly.

Were the railroads a trifecta innovation?

Perhaps the most famous case of economic monopoly in the US was the

rise of the railroads after the Civil War. A brief video on the evolution of railroads:

https://www.history.com/shows/modern-marvels/videos/evolution-of-railroads

The great railway tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt dedicated his career to assembling a monopoly of

steamships, and then set about purchasing railway lines; railways linked together steamship routes and were seen as secondary to steamships. As technology improved and economic development began to move into the interior of the US in the late-nineteenth century, railroads became ascendant. However, as one can glimpse in this letter to the editor at Scientific American from 1858, there was a lingering impression in the popular mind that railways were inferior to canals and steamships.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/canals-versus-railroads-1858-05-29/

In the realm of transportation, the displacement of shipping by railroads seems like a perfect example of

market-displacement innovation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport#Expanding_network

Railways quickly became essential to the swift movement of goods and labour that was needed for industrialization. In the beginning, canals were in competition with the railways, but the railways quickly gained ground as steam and rail technology improved and railways were built in places where canals were not practical.

Railways improved continuously from their emergence in the US in the 1830s until the mass production of the automobile and its domination of transportation in the 1930s. This continual improvement in rail technology signifies

sustaining innovation.

Aside from transportation, the railways were an

efficiency innovation in so many spheres of life, dramatically driving down the cost of all sorts of goods.

It could be that

the monopoly status of railways resulted from railways manifesting the perfect trifecta of innovation -- market-displacement innovation, sustaining innovation and efficiency innovation.

The other famous monopoly in American history was Standard Oil.

Does oil fit the pattern of a perfect trifecta of innovation?

In a

market-displacement innovation, by the 1850s, cheap, smokey "coal oil" derived from coal and used only for outdoor lanterns improved over time and displaced more expensive whale oil reserved for indoor lamps. Known as kerosene, it was refined to burn cleaner than whale oil.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_oil#History

The term [coal oil] was in use by the late 18th century for oil produced as a byproduct of the production of coal gas and coal tar. In the early 19th century it was discovered that coal oil distilled from cannel coal could be used in lamps as an illuminant, although the early coal oil burned with a smokey flame, so that it was used only for outdoor lamps; cleaner-burning whale oil was used in indoor lamps.

Coal oil that burned cleanly enough to compete with whale oil as an indoor illuminant was first produced in 1850 on the Union Canal in Scotland by James Young, who patented the process.

In a

sustaining innovation, a superior oil product derived from petroleum and labeled "kerosene" replaced coal oil labeled "kerosene". (In fact, for the longest time, kerosene derived from petroleum was popularly known as "coal oil".)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerosene#Kerosene_from_petroleum

Ignacy Łukasiewicz, a Polish pharmacist residing in Lviv, and his Hungarian partner Jan Zeh had been experimenting with different distillation techniques, trying to improve on Gesner's kerosene process, but using oil from a local petroleum seep. Many people knew of his work, but paid little attention to it. On the night of 31 July 1853, doctors at the local hospital needed to perform an emergency operation, virtually impossible by candlelight. They therefore sent a messenger for Łukasiewicz and his new lamps. The lamp burned so brightly and cleanly that the hospital officials ordered several lamps plus a large supply of fuel.

As kerosene production increased, whaling declined. The American whaling fleet, which had been steadily growing for 50 years, reached its all-time peak of 199 ships in 1858. By 1860, just two years later, the fleet had dropped to 167 ships. The Civil War cut into American whaling temporarily, but only 105 whaling ships returned to sea in 1866, the first full year of peace, and that number dwindled until only 39 American ships set out to hunt whales in 1876.[28] Kerosene, made first from coal and oil shale, then from petroleum, had largely taken over whaling’s lucrative market in lamp oil.

Electric lighting started displacing kerosene as an illuminant in the late 19th century, especially in urban areas. However, kerosene remained the predominant commercial end-use for petroleum refined in the United States until 1909, when it was exceeded by motor fuels.

In an

efficiency innovation, petroleum later fueled the automobile revolution wrought by Henry Ford's assembly lines. Oil and the mass-produced automobile would together cascade efficiency innovations throughout the economy, much the way that railways had earlier and smartphones would later.

Efficiency innovations create new opportunities for some people and unemployment for others. Motorized transport -- and thus petroleum -- transformed the agriculture sector of the early 20th century and rendered many workers obsolete.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_unemployment#20th_century

Rural American workers had been suffering job losses from the start of the 1920s; many had been displaced by improved agricultural technology, such as the tractor.

The transformation of agriculture by petroleum-powered vehicles is but one small piece of the modernization of transportation sector.

For example, in the previous century, the railroads and the Suez Canal created new efficiencies in transportation that led to lower prices.

http://www.georgistjournal.org/2012/09/21/henry-ford-caused-the-great-depression/

In 1869 the opening of the Suez Canal drastically reduced the price of Asian goods in Europe. Basically, it cut the distance from Western Europe to Asia in half, cutting the cost of production. But there was more: that same year, in the United States, at Promontory Point in Utah, the transcontinental railroad was completed, with the driving of the last, “golden spike”. Before the railroad, it took at least two months to go from New York to San Francisco. After the railroad it took seven days.

But greater efficiencies also mean more unemployment. In the following narrative, new transportation technology like railroads and tractors eliminates jobs. (It also drives up the price of provincial land because that land can now be connected to the greater national and international transportation infrastructure and be brought into productive use.)

In 1873 there came a bust: unemployment was increasing and wages were falling.

People are still coming from Europe, and a lot of people are migrating west. Plenty of people want to buy a piece of land, build a house and a barn, and plant a crop. They ask to buy some of your land (only a day’s ride from the railroad). Will you accept their offers?

What if you know that four or five years from now, connecting rails will be built and your land will be linked to the east-west railroad? Are you willing to sell your land to the highest bidder now — or will you hold out for a better offer?

But… Meanwhile… Where are all the people going to work?

Population is increasing, and machines like the railroad and farm machinery are replacing more workers than it takes to build and operate them. Products can be produced for less, therefore they sell for less, but that doesn’t help the unemployed workers who have lost their buying power. Reduced demand further depresses production and more workers are laid off — this time in the cities.

The same might be true of cars/oil. Mass production of the automobile brought down the price of automobiles.

In 1914, Henry Ford introduced the assembly line. Interchangeable parts had been used before in industry, but Ford was the first to use mass-produced parts in something as precise and complex as an automobile engine. Ford paid $5 per day — twice what Chrysler and Chevrolet were paying. He could afford to. For 13 years he made essentially the same car. Half the cars in the whole world were Fords. The Runabout, which was the economy car of the Model T line, cost $900 in 1910. Its price reached a low of $265 in 1924. There was some inflation in those years; according to the CPI inflation calculator, that $900 amounted to $1,554 in 1924 dollars — a price reduction, in real terms, of 82%! A car cost less than a team of horses — and you could buy one on credit.

Four cars were produced every minute; 240 per hour; nearly 6,000 per day. The country was paving roads and building bridges. More cars were creating more jobs making steel, glass and rubber.

Ford's mass production of automobiles inspired mass production ("Fordism") throughout the American economy, driving down prices in all sectors. The new spatial mobility afforded by automobiles transformed farmland into suburbs, driving up rural land prices. The new high price of land pressured employers to lay off workers who were already becoming useless to employers.

Production was revolutionized, thanks to old Henry Ford. All kinds of machinery was made on assembly lines.

America was still an agricultural economy. Farm machinery was getting better and cheaper. Workers were being displaced. They were going to the cities to seek work in the new factories. As cars got cheaper, more and more people bought them, and more and more roads were being paved. Now, it was far less important for farms to be close to cities. So, as the economy boomed, cities increased in population, and more roads were built. Urban factory workers could now live miles from the industrial areas, on what was previously farm land. Cheap farm land was transformed into pricey suburban developments!

Cars had never been cheaper than they were in 1927, but — nevertheless — fewer people were able to buy them. Machines continued to replace workers, as they had been doing for a decade. As the cost of production went down, business expanded; production and sales increased.

But there’s one thing they couldn’t produce — the land. Land values were going up everywhere. So the producers “downsized” — they laid off the workers and kept the machines.

Unemployed workers don’t buy a new car; unemployed auto workers don’t buy a new refrigerator; unemployed refrigerator workers don’t buy new shoes. Pretty soon you have a full-scale depression.

In sum, oil manifested the qualities of a perfect trifecta of innovations: It displaced whale oil and replaced coal, and fueled 20th-century modernization with greater efficiencies that led to long-term progress -- albeit with a profound short-term unemployment crisis (the Great Depression), compounded with the rise of a monopoly (Standard Oil).

Is Uber a trifecta innovation?

Uber is a sustaining innovation insofar as it provides a superior service within the taxi market (as Christensen asserts).

Is Uber an efficiency innovation? The use of a smartphone app instead of a taxi call center to connect customer and driver would seem to be a classic efficiency innovation that cuts out the middleman and drives down costs, and the same might said of sub-contracting drivers. Uber might be the Walmart of the taxi world, ruthlessly driving down prices. This seems to be how Uber moved downmarket and then attracted new customers who would never have used taxis.

(SpaceX's reuse of second stage rockets might likewise be an efficiency innovation. Earlier, the concept of "downmarket sustaining innovation" was advanced to note the paradox of simultaneous improving quality and diminishing prices that characterizes both Uber and SpaceX; this could be a result of simultaneous sustaining innovation and efficiency innovation. "Downmarket sustaining innovation" would then be expected to be a facet of "trifecta innovation", and would have characterized the railroads and petroleum/cars during their heyday.)

Uber may become a market-displacing innovation in relation to automobile ownership, which may come an anachronism in urban areas. Uber may become a car killer.

https://techcrunch.com/2018/05/30/heres-where-its-cheaper-to-take-an-uber-than-to-own-a-car/

Because of ride-sharing and self-driven cars, German carmakers are planning their transition to a future of reduced automobile production and ownership.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-17/-peak-car-and-the-end-of-an-industry

By 2030 in the U.S., where data is most readily available, Berylls predicts that total sales of cars – individually owned and shared – will fall almost 12 percent to 15.1 million vehicles.

BMW’s own estimates show that in a decade, one car-sharing vehicle will replace at least three privately owned ones, and mobility services, including autonomous cars, will account for a third of all trips. According to New York-based consultancy Oliver Wyman, mobility will be a 200 billion euro ($227 billion) business by 2040.

“Carmakers are desperate for their mobility divisions to be monetized,” said Michael Dean, a senior automotive analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “They must be involved in future mobility to avoid being left behind by the likes of Uber and Lyft.”

Already, Uber and its Chinese rival DiDi Chuxing Inc. are together valued at about $124 billion—just shy of BMW and Daimler’s combined market value, he said.

Ride-hailing services might be the perfect form of mass transportation in medium-density areas where high-capacity transit options like buses do not work out.

https://arstechnica.com/cars/2018/08/this-city-has-a-vision-for-mass-transit-that-doesnt-involve-city-buses/

Is Airbnb a trifecta innovation?

Airbnb may become a displacement innovation insofar as it is on the cusp of

displacing the hotel market.

But Airbnb might also someday help to

displace homeownership among Millenials if it develops the SRO model in terms of "co-living" dormitories. Co-living would not be a temporary arrangement for twenty-somethings, but a permanent way of life.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilhowe/2018/05/28/inside-the-millennial-inspired-co-living-boom/#2d690c5c3851

The big question everyone’s asking of this new Millennial iteration of co-living: Will the trend simply die out when Millennials decide to “grow up”?

Probably not. Co-living doesn’t so much reflect Millennials being slow to reach adulthood as it reflects Millennials redefining adulthood. To be sure, cost comes into play for this cash-strapped generation. But it’s not just that housing is more expensive.

Millennials simply don’t attach as much importance to the pride of property ownership and are turned off by the travails of property upkeep. Flexibility is also key: A Millennial moving to a new city may not want to commit to 12 months at an apartment, sight unseen, and risk losing a sizable deposit if things don’t work out. It’s a far less risky proposition to go month-to-month in a co-living space. (And if there’s one thing Millennials hate, it’s risk.)

Millennials don’t mind being dependent on others—whether it’s Mom and Dad or a group of strangers. It also doesn’t hurt that Millennials, who have been closely monitored their entire lives and have been raised to be team players, don’t place much importance on personal space and privacy. Most are perfectly happy to live in a micro-apartment or a crowded co-living space as long as there is a nearby gathering place to socialize—whether it’s downstairs in an outdoor common area or a few blocks away in a coffee shop. Proximity to the urban core is another Millennial motivator. Many are willing to sacrifice traditional living quarters in exchange for walking (or biking) distance to work and a great urbanscape view.

Co-living is a win for tenants, city governments, and landlords eager to reap the benefits of higher housing density, fewer commuters, more salary earners, and more rental income per square foot, among other things. It is generating new demand for remodelers and interior reconstruction firms. It could even help ease the impending U.S. caregiver deficit caused by a wave of retiring Boomers. Co-living is not good news, however, for a homebuilding industry expecting a Millennial housing boom to save the day. In any case, this trend is likely here for the long haul.

Airbnb is an efficiency innovation insofar as it offers lower prices than hotels.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/hbsworkingknowledge/2018/02/27/the-airbnb-effect-cheaper-rooms-for-travelers-less-revenue-for-hotels/#2cf04aaed672

Airbnb is revolutionizing the lodging market by keeping hotel rates in check and making additional rooms available in the country's hottest travel spots during peak periods when hotel rooms often sell out and rates skyrocket, a new study shows.

That's bad news for hotels, which have traditionally earned their biggest margins when rooms were scarce and customers were forced to pay higher rates—such as in Midtown Manhattan on New Year's Eve. And it's good news for travelers who don't have to pay through the roof to get a roof over their heads during holidays or for big events.

"The benefits to travelers and the reduction in pricing power of hotels is really concentrated in particular cities during certain times," says Chiara Farronato, a co-author of the study. "When hotels are fully booked, Airbnb expands the capacity for rooms."

Released today, the research shows that in the 10 cities with the largest Airbnb market share in the US, the entry of Airbnb resulted in 1.3 percent fewer hotel nights booked and a 1.5 percent loss in hotel revenue.

Airbnb would also be an efficiency innovation if it developed the SRO model in contemporary cities. Living in a dormitory in the city where everything is nearby is very efficient -- especially in a world where urban areas are flourishing and rural areas are becoming economically obsolete.

This is because the city manifests "

economies of density" in which proximity drives down costs (e.g., mass transit within the city).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economies_of_density

In microeconomics, economies of density express cost savings resulting from spatial proximity of suppliers or providers. Typically higher population densities allow synergies in service provision leading to lower unit costs. If large economies of density exists there is an incentive for people to concentrate and agglomerate.

Typical examples are found in logistic systems where the distribution or collection of goods is needed, such as solid waste management. Delivering, for instance, mail in an area with many postboxes results in overall cost savings and thus lower delivery costs.

Different network infrastructures such as electricity or gas networks show as well economies of density.

Moreover, economies of density allow for the transformation of one type of asset into another. For example, artists can flourish in the city because more than in any other environment, in the city they can exchange their cultural creativity for financial gain. Wealthy people in the city can exchange their wealth to purchase fine art and thereby gain greater respectability, which in turn broadens their social circle and increases their business opportunities.

In sociological terms, the modern global city is -- like an elite university -- a nexus where various forms of "capital" can be invested and exchanged for one another.

Various forms of capital include: financial or economic capital (jobs, property, money), cultural capital (education, art, "breeding"), social capital (social connections and networks), informational capital (knowledge) and symbolic capital (moral prestige).

https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm

Depending on the field in which it functions, and at the cost of the more or less expensive transformations which are the precondition for its efficacy in the field in question, capital can present itself in three fundamental guises: as economic capital, which is immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the forms of property rights; as cultural capital, which is convertible, on certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the forms of educational qualifications; and as social capital, made up of social obligations (‘connections’), which is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalized in the forms of a title of nobility.

The different types of capital can be derived from economic capital, but only at the cost of a more or less great effort of transformation, which is needed to produce the type of power effective in the field in question. For example, there are some goods and services to which economic capital gives immediate access, without secondary costs; others can be obtained only by virtue of a social capital of relationships (or social obligations) which cannot act instantaneously, at the appropriate moment, unless they have been established and maintained for a long time, as if for their own sake, and therefore outside their period of use, i.e., at the cost of an investment in sociability which is necessarily long-term because the time lag is one of the factors of the transmutation of a pure and simple debt into that recognition of nonspecific indebtedness which is called gratitude. In contrast to the cynical but also economical transparency of economic exchange, in which equivalents change hands in the same instant, the essential ambiguity of social exchange, which presupposes misrecognition, in other words, a form of faith and of bad faith (in the sense of self-deception), presupposes a much more subtle economy of time.

So it has to be posited simultaneously that economic capital is at the root of all the other types of capital and that these transformed, disguised forms of economic capital, never entirely reducible to that definition, produce their most specific effects only to the extent that they conceal (not least from their possessors) the fact that economic capital is at their root, in other words – but only in the last analysis – at the root of their effects. The real logic of the functioning of capital, the conversions from one type to another, and the law of conservation which governs them cannot be understood unless two opposing but equally partial views are superseded: on the one hand, economism, which, on the grounds that every type of capital is reducible in the last analysis to economic capital, ignores what makes the specific efficacy of the other types of capital, and on the other hand, semiologism (nowadays represented by structuralism, symbolic interactionism, or ethnomethodology), which reduces social exchanges to phenomena of communication and ignores the brutal fact of universal reducibility to economics.

In terms of lifestyle enhancement, "co-living" in an SRO might be a

sustaining innovation for young adults who would be renting anyway.

In co-living, the social events and entertainment of tenants are organized by the company that rents bedrooms to them. Co-living is essentially a way of purchasing a social life that resembles a roster of activities that one might find on a cruise ship -- an especially appealing arrangement for people who are new to a city or region.

In the following example, the co-living arrangement is in the suburbs and seems considerably more expensive than having roommates merely renting a house, and is therefore not the less-expensive efficiency innovation that it might be in some (urban) situations. But it is precisely the greater expense of co-living in this example that reveals the appeal of co-living to young adults. In other words, it is a sustaining innovation, a mainstream product (renting) that got better.

https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/08/23/co-living-millennials-san-jose-what-works-219378

Why should Airbnb and Uber be regulated?

A powerful new product, technology or business model may create the conditions for market dominance -- a kind of monopoly that should be regulated rigorously, the way a public utility is held to a higher standard. Later, this monopoly gives way to open market competition and should be deregulated. Even later, the technology or product becomes obsolete, yet continues to play a vital role as a government-subsidized legacy system that serves disadvantaged communities.

Airbnb might not be a true monopoly in the market of short-term home rental platforms because the barriers to enter this market are not daunting (basically, setting up a website). What gives Airbnb its domination in this market is its reputation. (Indeed, there are other home-rental platforms that thrive precisely because they are less well-known and can thus avoid government scrutiny.) This might be true of other contemporary "monopolies" like Amazon, in that the term "monopoly" is used not because they own the totality of the infrastructure of an entire market, but in order to describe their success in branding themselves

as the market (the way that the Kleenex company made itself synonymous with facial tissue).

Airbnb is now on the verge of penetrating the mainstream hotel market. It should now be regulated as a hotel chain. However, insofar as the hotel industry is about to face greater competition from short-term home rentals, perhaps the hotel industry as a whole might be due for some measure of deregulation.

Uber was originally a high-end a taxi company, according to Christensen. Yet Uber escaped the stringent regulations of the taxi industry, which is essentially regulated like a public utility. In fact, Uber is unique in that sustaining innovators like Uber who emerge within a mainstream market almost immediately come under attack by incumbents. Uber was spared for so long from a strategic response by other taxi companies because taxi companies were lulled into complacency by the government's support of them as monopolies, according to Christensen. (SpaceX was likewise initially dismissed as a joke by government-owned or government-backed rocket industries.) In retrospect, perhaps Uber should have always been regulated as the taxi company that it is. But insofar as taxis now face massive competition from companies like Uber and Lyft, the taxi industry should be deregulated. The days of monopoly are over.

This theory of regulation is quite different from the reasons given in the current wave of regulations that are being imposed on Airbnb and Uber.

It might be both possible and necessary to be creative in suggesting

how Uber and Airbnb should be regulated.

How should they be regulated?

One form of regulation would be to impose environmental constraints on Uber and Airbnb.

In particular,

all Uber vehicles should be EVs or hybrid plugins, and

all Airbnb rentals should be 100% electrified (no fossil fuels).

Most of the taxis in NYC are hybrid electrics. "As of September 2012, there are around 7,990

hybrid taxi vehicles, representing almost 59% of the taxis in service—the most in any city in North America."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxicabs_of_New_York_City

This was a product of government policy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hybrid_taxi#New_York_City

The City Council passed a bill in 2003 requiring the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission to set aside a proportion of new taxi medallions to be granted to vehicles that use cleaner fuels. As an incentive for fleet owners to buy hybrids, the Commission auctioned in 2004 the first taxi medallions for hybrids at discounted price of around US$170,000 less than the regular medallion price of US$400,000.

As integral part of the 2007 PlaNYC, Mayor Bloomberg set the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent by 2030. For this purpose, its component GreeNYC plan established that all new taxi vehicles entering the fleet beginning in October 2008 should have a fuel economy of 25 miles per U.S. gallon (9.4 L/100 km; 30 mpg‑imp), rising to 30 miles per U.S. gallon (7.8 L/100 km; 36 mpg‑imp) for cars entering the fleet in October 2009. Since hybrid cars were at that time the only vehicles that could meet those fuel standards, it was expected that most of New York's 13,000 taxis would be hybrids by 2012.

Unfortunately for NYC, the federal government is the only level of government that has the authority to impose mileage standards on vehicles. The requirement to purchase hybrid EVs that the city imposed on the taxi companies was rejected by federal judges.

In October 2008 a federal judge blocked New York City from implementing the fuel economy requirement. The ruling established that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in their key legal argument, "that the new regulations were pre-empted under federal law, which reserve regulation of fuel economy and emissions standards to federal agencies."

In July 2010 the city's appeal was rejected by a federal appeals court. The court upheld the initial ruling on the grounds that "the city's rules amounted to an effort to mandate fuel economy and emissions standards, something that only the federal government is allowed to do."

A new development complicates this federal law. At least two states -- Hawaii and California -- have mandated the transformation of their energy portfolio to 100% renewable sources of fuel by 2045. Vehicles are the the most stubbornly petroleum-reliant segment of the energy market, and the transition to EVs needs to be accelerated to accomplish the transition.

It needs to be emphasized in this context that if Hawaii and California were to mandate that all taxi and taxi-subcontracting services like Uber were to use only EVs or hybrid plug-in vehicles, this would not be done for fuel economy or emissions standards. Rather, it would reflect a policy initiative to electrify the grid and shift to renewable sources of electricity.

Everything needs to be electrified.

"Electrify Everything"

The decarbonization of the global economy involves three strategies:

1. Electrify everything.

2. Decarbonize electricity.

3. Reduce demand.

https://www.treehugger.com/energy-policy/reduce-demand-clean-electricity-electrify-everything.html

Electrification would increase the demand for electricity, while lowering the overall demand for energy.

This is because electric motors are inherently more efficient than internal combustion engines (ICE).

An electric vehicle has an efficiency of at least 60%, while an ICE vehicle supposedly has an efficiency of only 20%, most of the energy being lost in the form of heat.

https://www.alternativesjournal.ca/science-and-solutions/electrify-everything

If you electrify everything and produce electricity from wind, water, and solar, your power demand goes down 42.5 percent. Most of that is due to the fact that electricity is more efficient than combustion. If I drive a car, the plug-to-wheel efficiency of an electric car is about 80 to 86 percent. In other words, 80 to 86 percent of the electricity going into the car goes to move the car and the rest is waste heat. In a gasoline car, only 17 to 20 percent of the energy in the gasoline goes to move the car, the rest is waste heat.

The best place to begin this process of electrifying everything might be in the urban core.

From the highest density areas starting downtown and moving outward gradually in a concentric ring there would be an ever-expanding zone of total electrification and reliance on renewable sources of electricity.

Economies of density and service industries are key factors in this strategy. Urban areas have an advantage in a service-based economy because proximity drives down cost the cost of delivery. Once again, a summary of economies of density:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economies_of_density

In microeconomics, economies of density express cost savings resulting from spatial proximity of suppliers or providers. Typically higher population densities allow synergies in service provision leading to lower unit costs. If large economies of density exists there is an incentive for people to concentrate and agglomerate.

Economies of density can combine with the efficiency of electricity to drive down consumption. For example, "urban agriculture" or "indoor agriculture" has the potential to undercut traditional farming because it joins together 1) proximity to consumers, 2) the elimination of inputs such as pesticides and 3) the falling cost of electricity from renewable sources.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vertical_farming

The imposition of an Electrify Everything policy would be less of a burden in high-density urban areas because they already enjoy economies of density related to delivering electricity and because so much of a city's infrastructure is amenable to electrification.

Therefore, high-density areas would be the initial focus of an Electrify Everything campaign.

For example, a map of California lists counties in order of population density, starting with:

1. San Francisco

2. Orange County

3. Los Angeles

4. Alameda

5. Sacramento

6. Santa Clara

7. Contra Costa

These areas in this order would be the initial focus of Electrifying Everything.

Vehicles are an obvious source of carbon emissions.

Therefore, there would be a three-part vehicle policy in high-density areas:

- Ban private cars (only public transport and taxis would be allowed).

- Ban parking (only drop-offs and deliveries would be allowed).

- Ban I.C.E. vehicles (only electric plug-ins would be allowed).

https://www.businessinsider.com/cities-going-car-free-ban-2017-8#oslo-norway-will-implement-its-car-ban-by-2019-1

Buildings also play an important role in carbon emissions.

https://www.c2es.org/document/decarbonizing-u-s-buildings/

- Fossil-fuel combustion attributed to residential and commercial buildings accounts for roughly 29 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Improvements in energy efficiency have led to emissions reductions in the residential and commercial sectors of 17.3 and 11.4 percent, respectively, since a 2005 peak.

- Further efficiency gains will moderate future emissions growth, but the increased use of appliances and electronics is expected to result in a net increase in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

- Major opportunities to reduce emissions from buildings include increased electrification and greater energy efficiency, including through the use of “intelligent efficiency” technologies. Capitalizing on those opportunities requires aligning incentives among builders, owners and tenants to favor upfront costs that reduce both emissions and long-term costs.

Thus, there would be a program of total electrification of buildings.