[[[trends and crises

[[[American dream

Americans are famous for their geographic mobility, of picking up and striking out for new places and better opportunities.

But they are less mobile today.[[[American dream

Americans are famous for their geographic mobility, of picking up and striking out for new places and better opportunities.

That is both a mystery and a problem.

By

covered wagon and jetliner, from East Coast to West, Rust Belt to Sun

Belt, Americans’ propensity to be on the move – to new jobs and new

places – has historically provided the economy with a critical dose of

oomph.

But as fewer and fewer Americans are loading up the moving van in search of opportunity, that advantage may be slipping away. In recent years, economists have become increasingly worried that a slide in job turnover and relocation rates is undermining the economy’s dynamism, damping productivity and wages while making it more difficult for sidelined workers to find their way back into the labor force.

But as fewer and fewer Americans are loading up the moving van in search of opportunity, that advantage may be slipping away. In recent years, economists have become increasingly worried that a slide in job turnover and relocation rates is undermining the economy’s dynamism, damping productivity and wages while making it more difficult for sidelined workers to find their way back into the labor force.

“It’s

possible that one reason people aren’t changing jobs is because they’ve

all found jobs that are great for them and they’re happy,” Betsey Stevenson,

an economist at the University of Michigan and a former member of

President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, said. “But the other

possibility is that people stay in jobs that aren’t as good for them

because they’re terrified of changing, and that’s bad for the overall

economy.”

Job security has been diminishing for a long time. The expectation was that this would spark more mobility, but there is less of it. "People are not moving as much out of what used to be entry-level and temporary jobs." There is a chicken-and-egg question of causation, of whether reduced geographic mobility is promoting this trend, or vice-versa.

Mobility

normally drops during downturns, and that was the case during the Great

Recession. Millions of jobs vanished, and those fortunate enough to be

working were less inclined to give up the one they had.

But

even as much of the wreckage wrought by the crash has been cleared,

fluidity has not bounced back to prerecession levels. Although there was

a common perception that the mortgage crisis had stranded many

Americans in place, economists found scant evidence to support that

notion. Moving declined similarly among both renters and homeowners.

Something else appears to be going on.

One of the more intriguing patterns was the correlation between low levels of "social capital" (social networks) and mobility. One might expect those with limited local contacts to be more eager to move, but just the opposite is the case.

One

of the more intriguing findings was the role of declining social trust

and what is known as social capital — the web of family, friends and

professional contacts. For example, the proportion of people who agree

with the statement, “Most people can be trusted,” has been shrinking for

more than three decades. Researchers found that states with larger

declines in social trust also had larger declines in labor market

fluidity. The lack of trust may increase the cost of job-hunting and

make both employees and employers more risk-averse.

Ms.

Wozniak added that the benefits of LinkedIn and Facebook friends may

not replace the personal connections that still remain the best way to

find a job.

The worry among some economists was that as home-ownership rates increased, geographic and income mobility among Americans would decline. However, because renters turn out to be just as immobile, that correlation now seems dubious.

But let's try to connect the increased desire for home ownership that marked the housing bubble with the increasing levels of social alienation that correlate with decreased mobility. (Orange County, California was considered "ground zero" of the real-estate meltdown; it is also the locality in the US with the least social connections or 'social capital'.)

American houses are getting bigger -- for now...

Why did Americans develop a mania in the 2000s not just for buying a house, but a gigantic house?

It's been said that home-ownership is the "American Dream". This is not correct. As historians like Jim Cullen and Lawrence Samuels have written, this idea is all very recent.

An NPR article from 2006, "Behind the Ever-Expanding American Dream House" offers clues.

The increasing size of American houses cannot be understood entirely by rational, economic explanations.

When asked to speculate on why houses are getting bigger and bigger, Fergerson and her dining companions at Bobby Van's, a classic, old Bridgehampton restaurant, throw out dozens of ideas. Real estate agent Barbara Bornstein says land is so expensive, builders have no choice: They have to build big houses to make a profit.

"You know, we

are very tenuous," says local architect Ann Surchin. "No one knows when

the next 9/11 will happen. And these houses represent safety — and the

bigger the house, the bigger the fortress."

Town planning-board member Jacqui Lofaro says that people who work in cities see bigger homes as a source of peace of mind.

"If

you have people coming out from the city, where they are bombarded by

people, the tendency is to isolate themselves," Lofaro says. "Their

house is their community. It is not the community's community, it is

their community."

Even those in the real-estate industry are just guessing.An economist interviewed in the article explains that good public schools exist in neighborhoods with massive houses; some middle-class families feel compelled to move there in order to send their kids to good schools. Subsequently, other middle-class families feel envious and inferior, and so they buy houses they cannot really afford.

But this supersizing of houses is recent behavior. Why did this behavior not exist before, when these conditions - good schools in expensive neighborhoods with tony houses - have always existed? The economist did not historically situate his explanation.

In contrast, a developer interviewed in the article does historically situate one of his observations. For him, there is something fishy going on nowadays.

Trunzo says there's a different mindset among the wealthy today, compared to when his father started the family business.

"Most

of the big houses were visible from the road," he says. "You didn't

wall yourself in with hedges and hide." Now, he says, the wealthy "want

their own private little enclave. And they don't even want the general

public to know that they are there."

For Trunzo, it's just a bit strange. But for John Stilgoe, a

professor of landscape history at Harvard University, it's emblematic.

"The

big house represents the atomizing of the American family," he says.

"Each person not only has his or her own television — each person has

his or her own bathroom. Some of these houses are literally designed

with three playrooms for two children. This way, the family members

rarely have to interact. And the notion of compromise is simply out one

of the very many windows these houses sport."

Today, Americans still want big houses, when they should be downsizing. And it makes no financial sense.

Americans still want bigger homes -- even though they should downsize instead

By Rick Newman

February 26, 2015 11:56 AM

Don’t do it, people!

New research from real-estate data firm Trulia shows that Americans still crave big homes,

even after a brutal housing bust proved the perils of overspending on

real estate. In a Trulia poll, 43% of people said their ideal home is

bigger than the one they live in now, while just 16% said they’d prefer a

smaller home. Forty percent said they’re satisfied with the size of

their current home.

There’s

nothing wrong with dreaming, of course, but the trend toward purchasing

ever-bigger homes seems to have resumed after the disruption caused by

the housing bust that began in 2006. The average size of a new home has

dipped in recent months, according to data from the National Association

of Home Builders, but at about 2,600 square feet, it’s still close to

record highs, as this chart shows:

The Trulia poll results are predictable in some ways. It’s no surprise,

for instance, that young people want more space, as do Generation X

families with growing kids. But you might think baby boomers on the

verge of retirement would be preparing to downsize en masse. Not so.

Among boomers, 26% say they want a bigger home, while only 21% want a

smaller home. Here’s a breakdown of the Trulia numbers by age:

That's a bit disturbing. It's disturbing because in economic terms, it's irrational.

From a more recent article in the Wall Street Journal:

U.S. Houses Are Still Getting Bigger

The median size of a new home is 2,467 square feet, 61% bigger than 40 years ago

The median size of new homes is now 11% bigger than it was a decade ago.

By Jeffrey Sparshott Jun 2, 2016 12:02 pm ET

Americans want bigger houses. Or at least that’s what they’re getting.

The median size of a new single-family house was 2,467 square feet last year, the biggest on record, according to Census Bureau data out this week.

With all that floor space, homes are 61% larger than the median from 40 years earlier and 11% larger than a decade earlier.

“McMansion” may not be a popular term post-housing bust. But American homes have not only been getting larger, they’re also including more bathrooms and amenities such as air conditioning. Some 93% of new houses had air conditioning in 2015 compared with 46% in 1975. About 96% of new homes last year had at least two bathrooms versus 60% four decades earlier.

That may go some way toward explaining rising prices. The median sales price of a new home was $296,400 last year, according to Census, a new high. Even when adjusted for inflation, new-home prices hit a record last year.

More recent data suggest the housing market is gaining strength amid steady job creation and low mortgage rates, though rising prices and short supplies are constraints. U.S. new-home sales in April posted their strongest month in more than eight years. And sales of existing homes, which account for the bulk of the market, rose for the second straight month in April, the National Association of Realtors said last month.

A separate Commerce Department report out last week showed housing starts rebounded in April, leaving builders on pace to break ground on 778,000 single-family homes this year. Still, the number of starts remain well below historical norms.

Let's look at so-called 'Baby Boomers' born after WW2 and before the mid-1960s who are not downsizing, at least according to this 2015 article.

They rocked at Woodstock, marched in protest on campus, distrusted authority and then, as adults, took out mortgages and bought lots of real estate. But now, some economists say, baby boomers aren’t selling their houses as earlier generations did — they’re not downsizing fast enough as they approach and pass traditional retirement ages — and that’s contributing to shortages of homes for sale as well as to rising prices.

Boomers are part of a “clogging up [of] the whole chain of home sales,” Sean Becketti, chief economist of giant mortgage investor Freddie Mac, told me last week.

“They appear to be staying in the family home longer than previous generations,” Becketti wrote in a new outlook report, “and the imbalance between housing demand and supply continues to boost prices.”

Because of its size and wealth, this postwar generation has always had a tremendous influence on American society. That is still true today, with boomers controlling two-thirds of all home equity in the US, with a value of $8 trillion. But they are not selling their big houses and moving into apartments, which is throwing the real estate and mortgage industry, as well as potential home buyers, off track -- and raising the price of real estate.

How to explain this hesitancy to downsize on the part of Baby Boomers?

Many of them are still recuperating from the 2009 Great Recession.

Lawrence Yun, chief economist for the National Association of Realtors, says there are multiple factors at work here, especially the lingering effects of the housing bust and the Great Recession. Homeowners of all ages lost billions of dollars of equity wealth from 2008 to 2011, he argues, and many owners are still rebuilding sufficient equity to allow them to sell and move without having to bring money to the settlement. Boomers are a part of that group, and some have been forced to postpone their moves and sales.

Also, by not selling their homes, Baby Boomers have thus driven up the price of all real estate, including the price of the apartments that they would have moved into. So they cannot afford to buy because they hesitate to sell (because they cannot afford to buy, etc.). It's a vicious cycle.

David Crowe, chief economist for the National Association of Home Builders, points to a feedback-loop effect that is discouraging some boomers from listing and selling: Fewer listings means more competition for a limited supply of homes in hot markets. That competition pushes up prices for everybody, including boomers who might like to downsize but can’t find a replacement home that’s both affordable and acceptable. So they wait.

Eventually, the other shoe will drop. Boomers will get older and be forced to sell for all kinds of reasons. This could lead to a national real estate 'correction', for better or worse.

But changes are coming. Fannie Mae’s Simmons observes that the boomer logjam is a temporary issue. “Boomers will not inhabit this vast inventory [32 million homes] forever,” and when their circumstances change — which they inevitably will, with age — watch out. “Their actions will reverberate through the housing market.”

The economists provide their insights. But at no point do they actually talk to or listen to the actual human beings whose actions they are explaining.

However, another article from 2015 did just that.

As part of a broader initiative to understand where future home and community demand is headed, The Demand Institute surveyed more than 4,000 Baby Boomer households about their current living situation, moving intentions, and housing preferences.

We found that the common wisdom, which holds that Baby Boomers will downsize and head for a condo in a sunny place, appears to be wrong. First, nearly two-thirds of Boomers have no plans to move at all. They will “age in place” in homes and communities where they have often lived for a decade or more. Second, those who are moving are not going very far. Sixty-seven percent of movers will stay in-state and over half will move within 30 miles of their current home. Being close to their communities and families is very important to them as they age. “Wanting to be closer to family” is as common a reason for Boomers to move as seeking a “change of climate.” Third, and perhaps most surprisingly, we find that many Baby Boomers are still seeking their “dream home.”

Of greater economic importance, nearly half of those that will move (46%) plan to increase the size of their home or spend more for a home that is the same size as the one they have now. Perhaps this seems odd—why are they upsizing at this life stage? What we are seeing is that many who are living in smaller homes than they would like, and many who are renting, are now acting on the housing plans they had to delay as a result of the economic difficulties of the past few years.

The desire to maintain a sense of community might also include the

desire to avoid change and to avoid unfamiliar faces and places. In

fact, "community" might be a code word for stasis.

But the drive to own a "dream home" has more to do with American culture and popular ideology. Just as Muslims want to make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lives, so Americans want to finally attain that "dream house", fully paid off -- "free and clear" as Willy Lowman said in "The Death of a Salesman". In the modern world, religion fades, but elements of practical life take on religious significance.

But the drive to own a "dream home" has more to do with American culture and popular ideology. Just as Muslims want to make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lives, so Americans want to finally attain that "dream house", fully paid off -- "free and clear" as Willy Lowman said in "The Death of a Salesman". In the modern world, religion fades, but elements of practical life take on religious significance.

Let's take a closer look at what older Americans face when they do downsize.

If the 1980s were about greed and accumulating possessions, the current era is about downsizing and letting go of those possessions, says Denver gerontologist Karen Owen-Lee, author of “The Caring Code: What Baby Boomers Need to Learn About Seniors.”

“The Baby Boomers already started turning 65, and their parents are in their 80s, and they need to assist their parents from moving to their house of 40 years to independent living or assisted living,” Owen-Lee said.

“That can be psychologically hard. Last week, a woman called me and said that her mother is paralyzed by the task of cleaning out the basement. So we talked about some options. We came up with having a therapist talk to the mother, not more than for 15 minutes initially, to help understand that paralysis. And gradually increase that time, as the mother can handle it, until she’s ready to tackle the basement.”

Brace for the emotional, physical and, if you’re not careful, monetary tolls of downsizing.

Does the new home mean moving from a longtime neighborhood full of friends, shifting to an unfamiliar church or other house of worship? How will you forge relationships in the new community?

Reluctance to give up possessions tempts some people to rent storage units that cost $40 to $230 per month.

For downsizing Baby Boomers, "community" indeed turns out to be a code word for familiarity.

The article goes on and on, but there is no further mention of community, oddly. The bulk of the article is about consulting professionals ("personal moving consultants", "downsizing specialists", therapists, etc.) for advice on how to let go emotionally of one's personal belongings accumulated over a long life.

The real dread that Baby Boomers and others experience when facing downsizing turns out to be the prospect of discarding their household items.

Their stuff is their ultimate community.

Each item comes with a memory, and each of these memories is woven together to form the narrative of a life.

The memorialization of personal objects seems to be a cross-cultural, universal phenomena.

But for contemporary Americans, the grand narrative culminates in the final attainment of owning an overly large "dream home" packed with a super-abundance of nearly forgotten relics.

"Be fruitful and multiply." (Genesis 9:7)

There is the narrative of personal fulfillment and self-actualization in the ownership of a big house packed with old, familiar items. But aside from the universal quest for existential meaning, there is another side to Americans buying overly big homes.

Americans are taking more road trips -- for now

Americans might be less mobile in terms of moving to new places, but they are plenty mobile in terms of their vacations.

Americans were hitting the road again in 2015hanks to cheap gasoline and changed attitudes toward how to enjoy life.

The great American road trip is back.

It’s partly that gasoline this driving season is cheaper than it has been in 11 years, according to the AAA motor club, and that the reviving economy is making people more willing to part with their money. But there is more than that at play here. This may be a cultural shift, as Americans experiment with the notion that maybe money can, in fact, buy happiness, at least in the form of adventures and memories.

It is a change that appears to have taken root in the years since the 2008 financial crisis.

“Postrecession, people are focused on memories that cannot be taken away from them, as opposed to tangible goods that expire and wear out,” said Sarah Quinlan, a marketing executive at MasterCard Advisors. “There’s a sense that you can take away my job, you can take away my home, but you can’t take away my memory.”

Whatever their motivation, Americans last year drove a record 3.15 trillion miles, according to the Department of Transportation, beating the previous mark, set in 2007. So far this year, both travel and gasoline consumption are up again.

Since the Great Recession, Americans have rethought

their infamous acquisitiveness, and traded in their hunger for buying

stuff for a thirst for adventures that make great memories.

But

this new quest for experience is not any less wasteful environmentally

and financially than is the obsessive accumulation of objects.

Importantly, in some respects, the younger generation are not so different from their progenitors.

The desire to get behind the wheel still comes as something of a surprise. The conventional wisdom was that driving mileage had probably peaked in 2007. The demographic bulge represented by the baby boomers is aging out of the driving years; people typically drive less as they hit retirement.

At the same time, millennials were not sharing the passion for the open road that previous generations of young adults had. Many, in fact, preferred to live in the nation’s downtowns, eschewing personal cars in favor of shared Ubers, or walking to their work and play.

But it turns out that both generations are driving more than anyone expected. “A lot of millennial behavior was really deferred assimilation,” said Steven E. Polzin, a transportation researcher at the University of South Florida. In other words, just like Mom and Dad, they were destined for a more traditional lifestyle — the marriage, the home, the garage — they just took a little longer to get there.

Eventually, the city dwelling millennials will move out to the suburbs, just like everyone else.

One such millennial is Jenna Bivone, a 29-year-old website and app designer, who two years ago left downtown Atlanta to live on the outskirts of the city with her boyfriend. “We used to walk everywhere, but the rents were too high and we wanted some land for my dog,” she said. “In a more suburban area we found good schools, stuff like that for future plans.”

Now she has a daily commute of at least a half-hour each way, and on weekends she and her boyfriend drive around Georgia and neighboring states looking for the best hiking. Over the last three years they have taken road trips in Wyoming and Colorado to hike in the national parks.

“When we travel we want to go to places we might never see again,” she said. “We’re not going to be young forever.”

But there are reasons to believe that this is not a long-term trend.

What are some trends in how Americans spend their money post-Great Recession?

Here's a graph describing the drop in spending on gasoline in the face of the 2008 oil price rise (and the following recession).

The graph had predicted reduced gasoline consumption in the future. That has not held up, apparently, with cheap oil.

But is the current fallback to earlier American patterns of high gasoline consumption a permanent trend?

Crisis exposes trends

There

is a rule of thumb in military science that war exposes new trends in

warfare and also accelerates those new trends (e.g., mechanization,

computerization, etc.).

Perhaps serious economic

crises likewise expose and accelerates long-term trends. However,

whereas the military refashions itself post-war in order to address

ostensible new trends in warfare, the post-crisis economy slips back

into complacence, reassured that things have returned to normal.

If

this is the case, then reduced gasoline consumption is indeed the way

of the future. It might have been put off for a while with cheap oil

resulting from the fracking boom and reduced demand from China and so

forth.

But in the long run, this might be the future: Less travel.

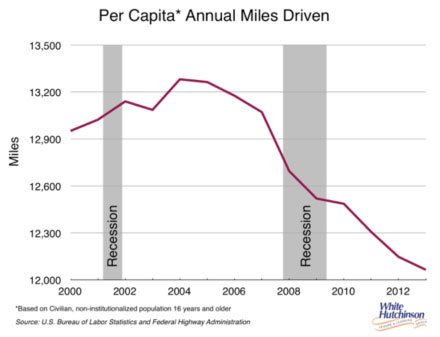

Here is a graph of miles of travel per American by year, from 2002 to 2012. It had been a downward trend since 2003.But in the long run, this might be the future: Less travel.

To some extent, one can see how within the period between 2000 and 2014, the number of miles being driven annually was inversely proportional to the price of oil.

But in a longer time frame, this correspondence between oil prices and miles travel becomes more problematic.

Historically, until the year 2000, oil prices have been $20 per barrel (adjusted for inflation). Oil prices have fallen since 2014, but they still hover in the $60 per barrel range. Until 2000, the number of vehicle miles fluctuated largely without regard to oil prices. After the Great Recession, oil prices and vehicle miles rose together as the economy recovered. Since the 2014 oil price decline, vehicle miles have risen.

But in a longer time frame, this correspondence between oil prices and miles travel becomes more problematic.

Historically, until the year 2000, oil prices have been $20 per barrel (adjusted for inflation). Oil prices have fallen since 2014, but they still hover in the $60 per barrel range. Until 2000, the number of vehicle miles fluctuated largely without regard to oil prices. After the Great Recession, oil prices and vehicle miles rose together as the economy recovered. Since the 2014 oil price decline, vehicle miles have risen.

A graph describing the number of teenage drivers with driving licenses from 2007 to 2014.

The current boom in travel might prove like a hiccup based on cheap oil.

All of this might help explain why Americans have become less mobile.

That is, if there is indeed a long-term trend toward reduced travel, this might be part of the reason for the current lessened geographic mobility in American life.

Americans might be traveling more on their vacations thanks to cheaper oil, but in their own lives, they are less mobile and more cautious.

But this might also be true for home sizes. During and after the 2009 Great Recession, home sizes fell. So the current ongoing expansion of home sizes might prove temporary.

What would a very strong trend look like?

Conceivably,

a strong trend would resist the influence of a recession and of the

subsequent recovery, even while it bucked other trends that happened

during the recession (e.g., reduced spending).

One result might be fewer strays as people spay and neuter their pets and keep their pets indoors. Here is a graph displaying cat intake and euthanasia levels at a shelter in Ontario from 2007 to 2014.

These are remarkably even, consistent graphs, especially considering the differing geographic and historical settings.

Cats and dogs have gradually transitioned from farm workers to domestic companions. It's been a long-term transition. But the 2009 recession might have exposed and accelerated that transformation.

In sum, what are a few potential trends in the United States?

1) Smaller houses.

1b) Less stuff in the house.

2) Less geographic mobility.

3) Not so many road trips (depends on the price of oil).

4) Incredibly pampered pets (and fewer strays).

5) Photographs of everything.

Disruptive Innovation

How might 'disruptive innovation' influence home buying patterns in the United States?

What do we mean by 'disruptive innovation' in its proper technical sense, as opposed to popular usage?

A disruptive innovation is an innovation that creates a new market and value network and eventually disrupts an existing market and value network, displacing established market leaders and alliances. The term was defined and phenomenon analyzed by Clayton M. Christensen beginning in 1995. More recent sources also include "significant societal impact" as an aspect of disruptive innovation.

Christensen distinguishes between disruptive innovation versus 'sustaining innovation'; in the latter case, mainstream technology improves, either in a revolutionary or evolutionary manner. Disruptive innovation, by contrast, comes from outside the mainstream market and sweep through it and destroys it, usually by providing a cheaper alternative to the dominant technology.

Not all innovations are disruptive, even if they are revolutionary. For example, the automobile was not a disruptive innovation, because early automobiles were expensive luxury items that did not disrupt the market for horse-drawn vehicles. The market for transportation essentially remained intact until the debut of the lower-priced Ford Model T in 1908. The mass-produced automobile was a disruptive innovation, because it changed the transportation market, whereas the first thirty years of automobiles did not.

The classic pattern of disruptive innovation is when an inferior but less expensive and more convenient technology finds a market niche on the fringes, develops over time and improves in quality, and then suddenly undermines the mainstream market.

Disruptive innovations tend to be produced by outsiders. The business environment of market leaders does not allow them to pursue disruption when they first arise, because they are not profitable enough at first and because their development can take scarce resources away from sustaining innovations (which are needed to compete against current competition). A disruptive process can take longer to develop than by the conventional approach and the risk associated to it is higher than the other more incremental or evolutionary forms of innovations, but once it is deployed in the market, it achieves a much faster penetration and higher degree of impact on the established markets.

To address the question of houses and disruptive innovation, we first need to look at how pets are disrupting families and replacing children.

Americans are having dogs instead of babies.

The fewer babies Americans give birth to, the more small dogs they seem to buy.

Birth rates in the US have fallen from nearly 70 per 1,000 women in 2007, to under 63 last year—a 10% tumble. American women birthed almost 400,000 fewer little humans in 2013 than they did six years before. The drop-off has come exclusively among 15- to 29-year-olds. This chart, taken from a recent report by the US Department of Health (pdf), does a pretty decent job of showing how much of the growing disinterest in having babies is due to younger women:

Meanwhile, the ownership of small dogs—that is, pets weighing no more than 20 pounds (9 kilograms)—is doing just the opposite. Americans have been buying more and more small dogs each year since 1999. The population of little canines more than doubled in the US over that period, and is only projected to continue upwards, according to data from market research firm Euromonitor.

“You do not have to go to many pet shows to realize that the numbers of small and tiny dogs are on the increase,” a report by Pets International opened in 2010 (pdf).

And rightly so. The number of small dogs has grown so fast that they are now the most popular kind nationwide.

It could just be a coincidence that Americans are birthing fewer babies at the same time as they’re buying a lot more little dogs. But there’s pretty good reason to believe it isn’t, Damian Shore, an analyst at market-research firm Euromonitor, told Quartz. “There’s definitely some replacement happening there,” he said.

It is young women who are deferring marriage who are buying the small dogs.

One telling sign that the two are not entirely unrelated is that the same age groups that are forgoing motherhood are leading the small dog charge. “Women are not only having fewer children, but are also getting married later. There are more single and unmarried women in their late 20s and early 30s, which also happens to be the demographic that buys the most small dogs,” Shore said.

This is one more reason for the increased spending on pets.

There’s also evidence people are treating their dogs a bit more like little humans these days. Premium dog food, the most expensive kind, has grown by 170% over the past 15 years, and now accounts for 57% of of the overall dog food market.

There are now tools to monitor your dog’s fitness, ice cream trucks exclusively for canines, and vacations designed exclusively for dog-having people. “The animals in our homes are family. They’re like children,” David Grimm, the author of the book Citizen Canine, told Wired this week.

Then there is, of course, the changed mode of living and its effect on pet ownership.

Of course, small dog ownership isn’t rising just because people want kid substitutes. Fashion trends aside, small dogs are also emblematic of a national migration to cities, where big dogs are harder to keep. Nearly 80% of Americans live in urban areas. “Smaller homes and apartments are also helping drive the growing popularity of smaller dogs,” Shore said.This is very incorrect. First of all, as we have seen, Americans homes are expanding in size. Second of all, 80% of Americans do not live in cities: roughly one quarter (26%) of Americans live in cities, about one fifth (21%) live in rural areas, and a little over half (53%) in suburbs. "Urban area" = suburb + city.

But more on this later. Back to disruptive innovation.

In terms of disruptive innovation, there is a double disruption going on here:

1) Dogs are disrupting families and replacing children.

2) Small dogs are disrupting and replacing big dogs.Small dogs are disrupting and replacing big dogs, but there is another disruptive innovation within the world of dogs.

Crossbred dogs are replacing purebred dogs.

So much of the enthusiasm for mixed-breed dogs can be traced back to the marketing in the 1980s of pug-beagle mixes -- "puggles" -- by the mass dog breeder Wallace Havens. This trend intersects with increasing urbanization.

Havens, a towering man of 70, has spent much of his career breeding cattle and owns a chain of Play Haven day-care centers. He is best known as the originator of the puggle, a pug-beagle cross with an irresistibly wrinkled muzzle, forlorn eyes and suitable dimensions for cramped city apartments. He first marketed puggles 20 years ago, but by late 2005, the dog suddenly had a cadre of celebrity owners, four-figure price tags and a brimming portfolio of magazine write-ups and morning-TV appearances. Puggle-emblazoned messenger bags and ladies’ track suits followed. For a time, in New York especially, you couldn’t swing a cat without hitting a puggle.

Around

the same time in Australia, serious breeders sought to create a new

breed of service dog to help people who were otherwise allergic to dogs.

In the late 1980s, an Australian dog breeder crossed a standard poodle with a Labrador retriever, struggling to fashion a capable guide dog for the blind with the poodle’s more hypoallergenic coat. He called the puppies Labradoodles. In 1998, a small partnership began exporting loping, shaggy-headed pet Labradoodles to the United States for upward of $2,500 each. Before long, Macy’s and Lord & Taylor sold thousands of Labradoodle stuffed animals to benefit cancer research; last year, Tiger Woods got a Labradoodle, and a metal Labradoodle replaced the Scottish terrier game piece in a special edition of Monopoly.

People

might want a mixed-breed 'designer dog' because they cannot make up

their minds on a particular breed. This is especially true when husbands

and wives clash over what kind of dog to get.

“I think the majority of the poodle problem is not the poodle itself,” she told me. “It’s the froufrou coat. It’s the haircut. Poodles are great dogs. But it’s hard to sell a poodle to a man.” Typically, she adds, a husband will want something like a beagle. “But the woman says, ‘Well I’m not buying that slick-haired dog, that beagle, because they’re not fuzzy and cute.’ ”

Havens’s granddaughter, who works at Puppy Haven, says she receives apprehensive phone calls from men, pleading for a small, apartment-friendly dog that will please their wives without being too poofy. They end up with puggles, she said. The breeds that satisfy these same criteria, like the Brussels Griffon, have seen some of the highest spikes in A.K.C. registrations over the last decade, as have smaller breeds in general. Everyone seems to be chasing the next small thing. Dedicated breeders have shrunk the Alaskan husky into a raccoonlike throw pillow, breeding it true and naming it the Alaskan Klee Kai. Even the puggle is now being superseded by the “pocket” puggle.

As

more women work for a living, within the household they exert more

power of choice. This includes the choice of dog, but it also includes

just about everything (hence the recent trend of husbands making "man

caves" out of a spare room or the garage or attic, whereas once upon a

time, the whole house was his "castle").

But a two-income family is also a family that is less likely to relocate for a job opportunity.

But a two-income family is also a family that is less likely to relocate for a job opportunity.

The

homes families live in have less yardage. City life presents this

challenge, but so does suburban life; since the 1950s, house sizes have

more than doubled, but lot sizes have shrunk. (Also, in the 1950s people

let their dogs and cats roam the neighborhood, producing more animals.)

“People don’t have the space they had before,” Bob Vetere of the American Pet Product Manufacturers Association told me. “Maybe you’ve moved from a 30-acre ranch into a two-room, fifth-floor walkup. Maybe you love the look of a mastiff, but want a 20-pound version of that.” Studies show that adults retain strong loyalty to breeds they’ve grown up with. And baby boomers, Vetere said, are unwilling to abandon the idea of pets as they retire. “Now,” he speculated, “maybe you could wind up being able to crossbreed the dog, to calm the dog down, to make it a little more friendly, a little more manageable.”

It could be that dogs will be disrupted by cats.

Pet cats now outnumber pet dogs.

Pet cats now outnumber pet dogs.

We may see in designer dogs the potential, however real or empty, of making dog ownership easier. In the ’80s, Vetere noted, the number of pet cats in America exceeded the number of dogs for the first time, after scoopable litters hit the market. People were working longer days; more families were two-income. Cats, already equated with self-sufficiency, could now be left all day without us having to muss with that box as frequently or with such fetid intimacy. An equally hassle-free arrangement with your dog meant hiring a pet sitter.

Finally, one more disruption in the world of dogs: according to the American Veterinarian Medical Association, 85% of dogs are today are adopted from shelters, and are spayed and neutered upon adoption. (The American Pet Products Association claims that the number is closer to 37%, but continues to rise.) This is yet another disruptive innovation in the pet ownership, one that will downsize the dog population. (When one used to meet people walking their dog, they would introduce him and say, "He's a purebreed." Now they say, "He's a rescue.")

In fact, do people today even want dogs? The idea of a dog "breed" is only about a century old, and coming into existence in Britain in the Victorian age. (Previously, there were only local "types" of dogs, like shepherding dogs and retrieving dogs, that would be bred within a general type, not a strict breed with a closed and recorded lineage. Also, some "breeds" like the Border Collie are really 'landraces' that emerged in a locality without consciously being bred by farmers.) That was a time and a place when dogs morphed from farm workers of mixed background to living works of art that could be cultivated like prize-winning flowers. Today, dogs are family members -- but even that status is changing.

Katherine C. Grier, a cultural historian and author of “Pets in America,” told me: “The dogness of dogs has become problematic. We want an animal that is, in some respects, not really an animal. You’d never have to take it out. It doesn’t shed. It doesn’t bark. It doesn’t do stuff.” I found even the maker of Amazing Live Sea-Monkeys, which launched its tiny crustaceans in 1960 with the slogan “Instant Life,” now forcefully rebranding itself, targeting parents who refuse “to get stuck with caring for another living thing."What people want in a pet today is the affection of a dog with the low-maintenance of a cat. What to do?

Could a virtual pet or a pet robot replace cats and dogs as companion animals? Will robot dogs replace pets in super-dense cities?

In a study in Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Rault predicts that as urban populations grow the cities of the future may not offer enough living space for 9.5 billion people and their faithful pets, and he claims that technology may offer lower-maintenance replacements in the form of robotic dogs or virtual-reality pet simulators.Something like this happened in Japan, but only marginally.

Sony introduced the Aibo in 1999, at a price of 250,000 yen (about $2,000 at current exchange rates). The beaglelike robots could move around, bark and perform simple tricks. Sony sold 150,000 units through 2006; the fifth and final generation was said to be able to express 60 emotional states.Even in Japan, a densely populated, aging country with an animist tradition that maintains that all things have souls, the Aibo was never a big seller. But when the product was discontinued and owners could no longer find replacement parts for their robotic pets, funeral arrangements for their robotic pets were often made.

Even the Japanese, with a large population of lonely senior citizens living in cramped quarters in large cities, are not turning toward robotic pets. Robotic pets are a marginal phenomenon, even in animist-inflected Japan.

But that might change. As of February 2018, Sony has resurrected a new, improved Aibo that is winning hearts and minds.

The new Aibo is quite simply adorable. It has touch sensors on its head, chin, and back so you can pet it. It responds to touch and voice, and 22 actuators enable more realistic movement than previous models. Its eyes are OLED panels. It has a camera on its nose to help it recognize family members and search for its bone — which is called Aibone — while a camera on its back helps it navigate to its charging station like a Roomba. (Aibo gets two hours of playtime and takes three hours to charge.)

And is America really urbanizing? Are Americans flocking to cities?

How 'urban' is America?

According to the US federal government, as of 2015, 63% of Americans live in cities, which compromise just 3.5% of the land mass of the United States.

A majority of the U.S. population lives in incorporated places or cities, although these areas only make up a small fraction of the U.S. land area, according to a new report released today by the U.S. Census Bureau. The percentage of the population living in cities in 2013 was highest in the Midwest and West at 71.2 percent and 76.4 percent, respectively.

“The higher percentage of people living in cities in the West can partly be explained by the limited access to water outside of western cities and federally held land surrounding many of these cities, which limits growth outside incorporated areas,” said Darryl Cohen, a Census Bureau analyst and the report’s author. “This is especially true in Utah, where 88.4 percent of the population lives in an incorporated place.”

The definition of 'city', of course, revolves around density.

The population density in cities is more than 46 times higher than the territory outside of cities. The average population density for cities is 1,593.5 people per square mile, while the density outside of this area is only 34.6 people per square mile. Population density generally increases with city population size. The population density of cities with 1 million or more people is 7,192.3 people per square mile.

Additional findings:

Density

Cities with the largest land area are mostly in the West and have fewer people per square mile. Four places in Alaska are among the nation’s largest in land area, such as Sitka city and borough, which consists of 2,870.4 square miles of land and has 3.1 people per square mile.

Among large cities, density levels increased the most for those with strong population growth and stable boundaries. Population density increased by over 700 people per square mile in both New York City and Washington, D.C., between 2010 and 2013, the highest increases in density among cities of 100,000 or more population.

Population decline or increases in land area caused decreases in population density in other places.

It's a stunning development, that almost two-thirds of Americans live in cities that make up less than 4% of the land mass of the United States. In fact, it's counter-intuitive to almost everybody.

That's because it's only true depending on how one defines 'city'.

Words like 'urban' and 'city' and 'built on' are used interchangeably sometimes, or used with great specificity at other times but with divergent definitions.

For instance, there is a distinction between 'urban' and 'built on', as one finds in the United Kingdom with "The great myth of urban Britain'.

What proportion of Britain do you reckon is built on? By that I mean covered by buildings, roads, car parks, railways, paths and so on - what people might call "concreted over". Go on - have a guess.

Until recently, conflicting definitions have made the calculation tricky but fortunately, a huge piece of mapping work was completed last summer - the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (NEA).

Five hundred experts analysed vast quantities of data and produced what they claim is the first coherent body of evidence about the state of Britain's natural environment.

Having looked at all the information, they calculated that "6.8% of the UK's land area is now classified as urban" (a definition that includes rural development and roads, by the way).

The urban landscape accounts for 10.6% of England, 1.9% of Scotland, 3.6% of Northern Ireland and 4.1% of Wales.

Put another way, that means almost 93% of the UK is not urban. But even that isn't the end of the story because urban is not the same as built on.

In urban England, for example, the researchers found that just over half the land (54%) in our towns and cities is greenspace - parks, allotments, sports pitches and so on.

Furthermore, domestic gardens account for another 18% of urban land use; rivers, canals, lakes and reservoirs an additional 6.6%.

Their conclusion?

In England, "78.6% of urban areas is designated as natural rather than built". Since urban only covers a tenth of the country, this means that the proportion of England's landscape which is built on is…

... 2.27%.

This map from the NEA report - also seen on page 20 of the PDF report above - helps to visualise what the country actually looks like.

But even it cannot reflect the extraordinary finding that almost four-fifths of what is designated urban land is not built on.

One

useful distinction that might be made is between developed areas that

are either suburbs or cities, versus relatively undeveloped or rural

areas that are either wilderness or devoted to agricultural uses.

In

the UK, such developed areas make up ten percent (10%) of the UK

(described above as 'urban', but it includes suburbs). In the US, these

developed areas make up about four percent (4%) of the land area,

whereas in New Zealand such areas make up about 6% of the country's land

area.

This can be explained by a couple of facts.

The UK is slightly smaller than Oregon, with a population of 65 million.

New Zealand is about the size of Colorado, with a population of 4.5 million.

New Zealand is about the size of Colorado, with a population of 4.5 million.

(Interestingly,

Germany has the same area as Montana, but Germany has one hundred times

the population of Montana's 800,000 residents.)

New Zealanders in particular are famous for the low-rise, suburban nature of their development. Suburbs are a mode of land use that diverges considerably from the city-centric development of Asian and continental European societies, but which have characterized the English-speaking world since the Industrial Revolution.

The United States is, by contrast, comparatively vast.

So if the US federal government says that almost two-thirds of Americans live in 'cities' that occupy 4% of the land, this should be understood to include suburbs as well. Very little of the land in the US is developed.

Here is a more critical look at those government numbers.

America has grown even more urban. According to new numbers just released from the U.S. Census Bureau, 80.7 percent of the U.S. population lived in urban areas as of the 2010 Census, a boost from the 79 percent counted in 2000. That brings the country's total urban population to 249,253,271, a number attained via a growth rate of 12.1 percent between 2000 and 2010, outpacing the nation as a whole, which grew at 9.7 percent.

Overall, these results aren't very surprising.

But we're not just talking about cities here. The new figures represent the population in "urban areas," which the Census Bureau defines as "densely developed residential, commercial and other nonresidential areas."

There are officially two types of urban areas: “urbanized areas” of 50,000 or more people and “urban clusters” of between 2,500 and 50,000 people. For the 2010 count, the Census Bureau has defined 486 urbanized areas, accounting for 71.2 percent of the U.S. population. The 3,087 urban clusters account for 9.5 percent of the U.S. population.

Though these smaller urban clusters account for a relatively small portion of the total population, they make up the vast majority of the roughly 3,500 "urban" areas in the U.S. But is a town of 2,500 people really what we think of as "urban"?

According to the Census Bureau, a place is "urban" if it's a big, modest or even very small collection of people living near each other. That includes Houston, with its 4.9 million people, and Bellevue, Iowa, with its 2,543.

If roughly 80 percent of our population is urban, roughly 80 percent of our urban areas are actually small towns.

But with such a wide spectrum making up the definition of the word "urban," maybe it makes more sense to think of the U.S. as majority non-rural.

So to come up with the statistic that 80% of Americans live in urban areas, 'urban' was defined as city + suburb + small town.

What about the 'emic' or insider perspective on this matter?

That is, what do regular Americans think about how 'urbanized' America is?

Interestingly,

as far as governments are concerned, the word 'city' is a legal-political term, and, as such, its official meaning is divorced

from common sense use.

What, exactly, is a city? Technically, cities are legal designations that, under state laws, have specific public powers and functions. But many of the largest American cities — especially in the South and West — don’t feel like cities, at least not in the high-rise-and-subways, “Sesame Street” sense. Large swaths of many big cities are residential neighborhoods of single-family homes, as car-dependent as any suburb.

Cities like Austin and Fort Worth in Texas and Charlotte, North Carolina, are big and growing quickly, but largely suburban. According to Census Bureau data released Thursday, the population of the country’s biggest cities (the 34 with at least 500,000 residents) grew 0.99 percent in 2014 — versus 0.88 percent for all metropolitan areas and 0.75 percent for the U.S. overall. But city growth isn’t the same as urban growth. Three cities of the largest 10 are more suburban than urban, based on our analysis of how people describe the neighborhoods where they live.

What

the government says about how urbanized the US is diverges from both

the common experience of Americans and geographic reality.

It turns out that many cities’ legal boundaries line up poorly with what local residents perceive as urban. Nationally, 26 percent of Americans described where they live as urban, 53 percent said suburban and 21 percent said rural. (This comes close to the census estimate that 81 percent of the population is urban if “urban” is understood to include suburban areas.)

Furthermore, the new census population data shows that the fastest-growing large cities tend to be more suburban.

City growth, therefore, does not necessarily mean more urban living. In order to understand policing, schools, property taxes and other typical responsibilities of city governments, we need to look at cities as defined by their legal boundaries. But when we’re looking to understand the economic, social and demographic issues facing urban and suburban America, city boundaries can mislead. Looking instead at neighborhoods, classified by their characteristics into urban, suburban and rural, shows more clearly how suburban America — including many of its largest cities — actually is.

Are cities really growing? Or are suburbs growing?

One thing seems certain...

Young, Educated, Prosperous People Are Moving to the Cities

It seems to be a fact.

Influx of Younger, Wealthier Residents Transforms U.S. Cities

Educated, relatively high-earning workers are flocking to urban neighborhoods at a rate not seen since at least the 1970s

By Laura Kusisto

The Baurs are part of a wave of young, educated, relatively high-earning workers flocking to many American cities at a rate not seen since the U.S. Census Bureau began tracking such data in the 1970s. The shift began last decade and accelerated during the housing bust.

This sounds like a very strong trend, that is, an ongoing trend that actually accelerated during the economic crisis (whereas a 'strong trend' like pet ownership trends was unaffected by the crisis, and more moderate trends like buying bigger houses and going on road trips temporarily dropped during the recession, then came back).

The movement is injecting new life into tired urban cores, prompting renovation of older residential and commercial buildings while spurring new real estate developments as well as upgrades to transit systems, parks and cultural institutions.

A range of factors is driving the urban influx, economists say, from job growth and declining crime in cities to young professionals waiting longer to have children—or deciding not to have them at all. Tighter mortgage lending and concern about homeownership risks also weigh on young people, turning many into long-term renters.

For landlords and developers, rising rents and home values are a boon. But the costs can push out lower-wage employees as well as teachers, police and other middle-income public servants, making it harder for employers to attract such labor.

As many of the displaced move to suburbs, new strains are emerging there, on schools, transportation and services for the needy.

“The housing affordability issues are no longer limited to the high-cost coastal cities” such as New York and San Francisco, said Stockton Williams, executive director of the Urban Land Institute’s Terwilliger Center for Housing.

Those who have moved to revived city neighborhoods say they love the new amenities. And for some there is another plus: no need for a car.

Joe and Melanie Baur, in Ohio City, say they bike, take public transit and walk, including jaunts with their dog, Moses Cleaveland, named after the city’s founder, who spelled his surname with an extra “a.”

The car “was such an albatross,” Mr. Baur said. “I hated it.”

Relatively affluent, young, talented folks are moving to the cities, and in some respects driving out the less fortunate into the suburbs.

This raises another issue: The suburbs are the new slums.

Americans still tend to think about poverty as an inner-city problem. But some time around the dot-com bust and 2001 recession, the number of poor people living in the suburbs actually outstripped the total residing in cities. So why is suburban poverty often treated as out of sight, out of mind?

One reason may be that it’s more diffuse. In urban areas, the poor are often packed into predominantly low-income neighborhoods. In the 'burbs, they’re generally scattered through more economically diverse communities. In other words, the U.S. suburbs are home to lots of impoverished people, but they’re not home to lots of slums.

That’s beginning to change, though, according to a new brief by Elizabeth Kneebone of Brookings. During the 2000s, suburban poverty not only grew—it also became more concentrated. In 2000, 27 percent of poor suburbanites lived in neighborhoods with a poverty rate of at least 20 percent. During the 2008–2012 period, the figure was about 38.3 percent.

[M]ost suburban communities aren’t really equipped to handle the needs of the poor: The public transport systems are meager, the schools don’t offer English-as-a-second-language courses for immigrant children, and there aren't the same networks of charity organizations dedicated to working with struggling families. The only upside of living in the ‘burbs as a poor household is that you might not be surrounded by as many other poor households; research suggests that it's better to be broke in a neighborhood with a low overall poverty rate than a high one. In a high-poverty suburb, though, families are getting the worst of all possible worlds.

The cities are getting the rich folks, the suburbs are getting the poor.

But are the cities growing? And the suburbs?

From 2014, a Time magazine article "The Cities Are Slowing But Suburbs Are Growing".

While cities are still outpacing suburbs, the gap is closingThere is again the issue of how to define 'city'.

The United States’ biggest cities grew more slowly last year as suburban areas ticked up, according to figures released by the U.S. Census on Thursday, suggesting that city-dwelling Americans may be looking to the suburbs again. While city growth overall is still outpacing the suburbs, the gap between the two is shrinking after several post-recession years in which downtowns and older urban cores around the U.S. saw significant population increases.

“The slowing growth in these urban cores and the increasing gains in the suburbs may be the first indication of a return to more traditional patterns of city-suburban growth,” said University of New Hampshire demographer Ken Johnson.

The new Census figures show significant growth in suburban areas in the South and West. Almost all of the fastest-growing cities with a population of 50,000 or more were suburbs of major cities like Dallas, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Nashville and Houston.

Texas suburbs saw the largest growth between 2012 and 2013, especially in areas around Austin, a city millennials have moved to in recent years for its tech jobs and cultural opportunities. The U.S.’s fastest growing city is San Marcos, whose population grew 8% in 2013. Cedar Park and Georgetown were also in the top seven fastest-growing cities, and all three Texas cities surround Austin.So the article assures us that 'cities' are still growing -- but then it turns out that it is the suburbs of major cities that are growing most.

How did the 2009 recession affect patterns of habitation?

Historically, Americans have moved from downtown city cores to suburbs as they got older, had children and needed more space. Suburbs grew three times as fast as cities from 2000 to 2010, according to an analysis by William Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution. But the recession quickly reversed that as many older Americans felt frozen in place and decided to stay put, temporarily halting that city-to-suburban flow. At the same time, those in their 20s and 30s have flocked to downtowns in that same period, often lured by jobs and the ease of commuting in an urban area.

But Frey says the U.S. is a long way off from the kind of suburban sprawl it witnessed throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Many of those living in cities have likely decided to stay put for good, Frey says, or are still financially unable to move or buy a house. “We may never see that kind of suburbanization again,” he says.

So suburbs are still growing faster than the cities, and some of these 'cities' are actually suburbs of major cities.

But what about the jobs and money scene in these localities?Good Jobs and Smart People Move to the City,

the Rest of Us Go to the Suburbs.

According to this 2015 New York Times article, more new jobs are in city centers, while employment growth shrinks in the suburbs.

For decades, most Americans working in metropolitan areas have gone to work outside city centers – in suburban office parks, stores or plants, not downtown skyscrapers. But as people increasingly choose to live in cities instead of outside them, employers are following.

In recent years, employment in city centers has grown and employment in the surrounding suburban areas has shrunk, a striking change from the years before, according to a report published Tuesday by City Observatory, a think tank. The changes are seemingly small, but they represent an important shift in the American work force. As recently as 2007, employment outside city centers was climbing much faster than inside.

Economically, there has always been a virtuous-vicious cycle of jobs seekers moving to where the employment is, and employers going where the talent goes. Increasingly, talent and jobs are headed to the urban core.

Some cities — especially big ones hemmed in by water, like New York and San Francisco — have held onto a large share of employment near the city center. But now, urban job growth is increasing more quickly in those cities than before. And in other cities — including Chicago, New Orleans, Orlando, Charlotte and Milwaukee — employment is growing in the urban core and declining in the suburbs.

We pay close attention to the number of jobs gained or lost. But the location of jobs is just as important — including for making decisions about employment, housing and transportation policies.

Unfortunately, the increase in urban employment opportunities is mainly in the best paying jobs. That means that most folks would get priced out of cities (as was explained in an earlier article, above).

“How do you connect people to economic opportunity and the kinds of jobs that can give them secure footing and a path out of poverty?” said Elizabeth Kneebone, a fellow studying metropolitan policy at the Brookings Institution. “The first step is understanding where jobs are located, and can people afford to live where the good job growth is happening.”

The jobs in the heart of cities tend to be highly skilled and high-paying ones, in industries like finance and tech. Working-class jobs, like retail or construction, are more likely to be suburban. So with the recent growth of downtown jobs, the risk is that cities will continue to become havens for the wealthy and inaccessible to the middle and working classes.

Historically, there was a long exodus from the cities to the suburbs since the 1950s -- first of people, then jobs.

The vast majority of jobs are still outside city centers, the result of a retreat from America’s cities that has been going on for decades. At the beginning of the 20th century, people lived and worked in high-density areas and walked where they needed to go. By the 1950s, most lived in suburbs and commuted to work in cities. In the decades that followed, employers decamped to the suburbs, too. By 1996, only 16 percent of metro area jobs were within a three-mile radius of downtowns, according to the economists Edward Glaeser and Matthew Kahn.

The recession accelerated the recent decline in urban sprawl. Industries based outside cities, like construction and manufacturing, were hit much harder than urban ones like business services. Jobs disappeared everywhere, but more rapidly outside cities.

First, 'urban sprawl' really means suburban sprawl.

Second,

the recession did slow the expansion of suburbs. But this does not seem

to be an acceleration of a "recent" trend; the articles above suggest

continued suburban expansion. But the suburbs seem to be getting poorer.

But there seem to be new trends that make the enrichment of the cities more than a fleeting fashion.But the data indicate that more lasting forces are at work. People increasingly desire to live, work, shop and play in the same place, and to commute shorter distances — particularly the young and educated, who are the most coveted employees. So in many cities, both policy makers and employers have been trying to make living and working there more attractive.

Cities are also better able to hold on to jobs than they were before. “It means healthier cities,” said Joe Cortright, who runs City Observatory and is president of Impresa, which does regional economic analysis. “If the urban core is economically weak or fiscally troubled, that creates a burden for a whole metropolitan area.”

And, of course, YMMV -- Your Mileage May Vary.

Some cities have not followed the trend, like Dallas and Houston, where employment outside the city is still growing faster. In others, like Jacksonville and St. Louis, jobs have been declining in both locations, but more quickly outside urban centers. Cities with a high concentration of urban jobs include Austin, New Orleans and Portland, Ore. In Atlanta, Los Angeles and Miami, meanwhile, less than 10 percent of jobs are in the urban core.

This transformation seems to be the culmination of the shift to the post-industrial knowledge economy.

The 110-story Willis Tower in downtown Chicago is a microcosm of the shifting geography of jobs.

Originally called the Sears Tower, it was built in 1970 by Sears Roebuck and Co. But in 1988, Sears left it for a green suburban campus in Hoffman Estates, Ill. Then, in 2013, United Airlines moved its world headquarters and 4,000 employees into the tower. Other companies like Motorola Mobility and Archer Daniels Midland have also recently relocated to downtown Chicago from suburban campuses.

Chicago has gained more creative jobs, international tourism, university centers and residential development. The Chicago Loop, the city’s central business district, has been transformed from a financial district that emptied at 5 p.m. to a seven-day-a-week entertainment zone, said Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

The changes have been driven in part by employees wanting to live and work downtown, said Mr. Renn, who writes the Urbanophile blog: “Today there is more of an expectation on the part of both people and employers that they have to be more flexible and accommodating of their work force.”

Economists have described the benefits of workers clustering in a dense urban area: For a certain sector of knowledge jobs, ideas bloom from spontaneous, face-to-face interaction in coffee shops or elevators. But what does urban employment growth mean for other types of jobs?

But that is cold comfort to the majority of us who are not a part of that economy.

Some say more highly skilled jobs in an urban area will lead to more of all kinds of jobs. For every college graduate who takes a job in an innovation industry, five additional jobs are eventually created in that city for waiters, carpenters and teachers, according to Enrico Moretti, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley. As The New York Times reported this month, New York City is adding jobs at a furious pace, and they range from making software to busing tables.

But others say the shift overwhelmingly favors the highly skilled. “The problem with the general trend is that the poor are being priced out of cities,” said Mr. Glaeser, who teaches at Harvard University and wrote “Triumph of the City.”

American cities have succeeded in reshaping their urban cores as places people want to live and work. The question is whether these benefits will apply to everyone — or just to high earners.

Now, who exactly is moving to the cities?

More specifically, upper management is moving to the cities in order to be around young, educated, creative types. Upper management wants to be in the city in order to hire the new talent that lives in the cities. But the top brass also wants to rub shoulders with the youngsters in order to become more like the Young Turks -- dynamic and innovative.

Middle management, in contrast, is being farmed off to the cheaper suburbs.

"Why corporate America is leaving the suburbs for the city."

In a nutshell, the city is where the young, educated, creative, ambitious people are. They want to be in the city, not working in a cubicle in an office park in the suburbs. This is partly because American cities have really improved since the 1970s. Management want these kinds of diverse, dynamic workers because American corporations now see themselves engaged in "permanent revolution" (borrowing the rhetoric of Maoism) to constantly reinvent their companies. The west coast (San Francisco, Seattle) is the most creative region of the US, and this is particularly where corporate executives want to be located.

Also, work can be done over the internet now, so that the whole corporation does not have to be ensconced together in an office park. So, properly speaking, it is upper management that is moving to the city, not the corporation itself. With the corporate downsizing that has been going on for decades in the United States, there are fewer people to take along when the upper echelon corporation picks up and leaves the suburbs for the city. Middle-management jobs are not only remaining in the suburbs, but they are moving to the suburbs from the city.

Besides blue-chip icons like G.E., McDonald’s and Kraft Heinz, venture capital investors and start-ups are increasingly looking to urban centers, particularly on the West Coast, said Richard Florida, an urban theorist and professor at the University of Toronto.

“The period of companies moving to suburbs and edge cities has ebbed, but I had thought that start-ups would continue to locate in so-called nerdistans, like office parks,” he said. But a recent study by Mr. Florida showed more than half of new venture capital flowing into urban neighborhoods, with two San Francisco ZIP codes garnering more than $1 billion each, he said.

The return of a top echelon of executives to American cities reflects — and may well reinforce — disparities driven by widening inequality, underscoring how jobs are disappearing in other locales.

There is a certain irony that liberal urban planners like Richard Florida celebrate the idea of the American city as a font of creativity. The irony is that this now represents the corporatization of creative urban life. One parallel might be the rebelliousness that supposedly existed in the (late) 1960s in the drug use, music and promiscuity of a minority of young people associated with the counter-culture ("hippies"); by the 1970s, this kind of behavior lost any sort of spiritual or political meaning as it went mainstream ("sex, drugs and rock-n-roll") and was co-opted by corporations. The current medicalization of marijuana represents both the victory of the old counter-culture, but also the victory of corporations who will eventually monopolize this trade.

Richard Florida's ideas derive from insights gleaned from British sociology from the 1950s. It was observed then, in the emerging urban blight of the UK, that urban regions went through a cycle of decay: a long period of blight was followed by young, artistic types moving into blighted areas in order to take advantage of cheap rents (as in Detroit today); later, young, upwardly mobile businessmen would move in. The peculiarity is that the British critique of urban cycles had a critical edge to it: The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. The liberal American interpretation is one of shallow, complacent enthusiasm that seems clueless about how this cycle perpetuates and exacerbates income inequality ('equality of condition').

In the article, the conservative urban planner Joel Kotkin also weighed in, touting the continuing relevance of the suburbs.

Over all, there has been a slight pickup in employment and population in the central core of big cities, said Joel Kotkin, an author and urban geographer at Chapman University in California. But many close-in suburbs and neighborhoods are withering, particularly in the Northeast. More distant suburbs and exurbs are still thriving, especially in the Sun Belt.

“The elite functions are going downtown,” Mr. Kotkin said. “But at the same time, middle-management jobs are moving to the suburbs in places like Dallas, if they’re not leaving the country entirely.”

So rich people and jobs are moving to the cities, and the rest of us are getting priced out, so we have to move to the suburbs.

But it's even more dramatic than that...

...Even rich people are getting priced out of Manhattan!

On how a hot real estate in the big city market spills over into the suburbs.

The bidding wars that have become the norm in New York City are now also common in select suburbs within easy commuting distance. Buyers priced out of the city are heading for the ’burbs, driving up demand and creating a more fraught buying process in close-in towns that have long enjoyed reputations for good school systems, lively downtowns and ready access to the city.

“The city is this pot of water that’s spilling over on the sides, and that excess demand is going to the suburbs,” said Jonathan Miller, the president of Miller Samuel, a New York appraisal and research firm. “It’s all being driven by the lack of affordability.”

This is not rich people looking for the idyllic life in the tranquil suburbs. They would rather be in Manhattan, and the one quality they want in a house is quick access to the city.

Generally speaking, buyers are not lining up for luxury properties. High-end homes — upward of $2 million or $3 million, depending on the location — are still going begging across the metropolitan area, agents said. Demand for these homes is weakest in affluent suburbs without a train station. “The reason is clear: The high-paying jobs in the region are now disproportionately located in Manhattan,” Mr. Otteau said. “And if that’s where you’re going, there’s just not enough hours in the day to involve a car in that commute.”

At the same time, the luxury market in rail-centric towns is also slow, as they vie for fewer Wall Street bonus dollars and compete with a growing preference for urban living. Said Mr. Otteau, “Because of the dramatic improvement in urban life in the last 20 years, it’s no longer a given that when you’re ready to raise a family, you need to go out and buy a house in the suburbs.”

But many buyers who would prefer to stay in New York City simply can’t afford to. In Pelham, “almost all of our buyers are coming from the city, increasingly from Brooklyn,” Mr. Scinta said. “They are being priced out in terms of the additional space they need. They’ve outgrown their apartments and can’t afford to move up to the next-size apartment.”

The 1950s are so over.

A Stong, Conservative Defense of the Suburbs

And now, for a strong, conservative defense of suburbs is the essay

"A Planet of Suburbs" from the Economist magazine, December 2014.

The

developing world is suburbanizing, just as the United States did after

the Second World War. For the author, this is marvelous.The shift in population from countryside to cities across the world is often called the “great urbanisation”. It is a misleading term. The movement is certainly great: the United Nations reckons that the total urban population in developing countries will double between 2010 and 2050, to 5.2 billion, while the rural population will shrink slightly. But it is nothing like as obviously urban. People may be moving towards cities, but most will not end up in their centres. Few cities are getting more crowded downtown; between 2001 and 2011 Chennai added just 7% more people while Chengalpattu swelled by 39%. In developed and developing worlds, outskirts are growing faster than cores. This is not the great urbanisation. It is the great suburbanisation.

The author admits the oddness of suburbs, and confesses their apparent sterility.